It is such a pleasure to read about a city lover walking around and enjoying the diversity evident in all the people sitting on benches in parks or congregating in shopping centers. Elijah Anderson is the William K. Lanman, Jr. Professor of Sociology at Yale University. His first book Code of the Street was an award-winning examination of inner city violence. This acclaimed African-American sociologist returns to the city for this book, but looks at it from a different angle.

According to a 2010 Pew report, Philadelphia remains "a place where the poor and working class form the majority. One out of every four residents lives below the poverty line — a greater share than in most big cities — and the median household income is half the suburban average. The old economy has left a lot of Philadelphia behind." Anderson tackles the thorny problem of contemporary race relations in Center City Philadelphia where whites and blacks mingle in what Anderson calls the "cosmopolitan canopy" — public spaces that function as islands of civility where people can practice getting along with each other. Here we put behind us the barriers that separate the races and delight in the diversity of the American experience.

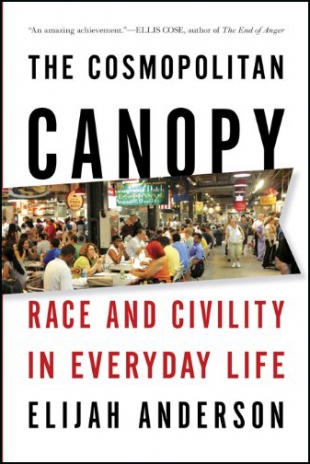

In the presence of strangers, city folk still adhere to the idea that white skin color brings to mind respectability, civility, and trust whereas black skin color is associated with poverty, danger, and distrust — especially in regard to young males. Anderson takes a walking tour through Philadelphia and startles us with all the details he notices about the people and the places, especially in the park. He is taken back by the comfortable ambiance of the Reading Terminal Market where very different people are eating one another's food. He calls it "a kind of multiethnic festival." Anderson sums up what he feels here:

"These various individuals generally get along well with one another in this space. They need not interact intimately; rather, they simply share the market with one another, interacting in the act of buying and selling. They give one another the 'aura' referred to by Georg Simmel, allowing each person to swim about in this sea of diversity while being largely left alone. They come, interact in a broad sense, obtain what they want, and return to the world outside this setting."

What the author really likes about Reading Terminal Market is the civility evident there. People behave courteously, smiling at one another and offering help or directions when needed. Anderson finds some of the same spirit in Rittenhouse Square, the city's premier public park. He sits on a bench and marvels at the social dance people do to avoid bumping into one another. In nice weather, the place seems to be a carnival.

In each of the cosmopolitan canopies he describes, we sense Anderson's hope that they may open hearts and minds as an antidote to rigid separations between blacks and whites, affluent gentrifiers and homeless people, cab drivers and passengers. Best of all is the author's relaxed and inspiring enjoyment of the city as a place of constant surprise, a multiplicity of pleasures, and wonder-inducing urban spaces.