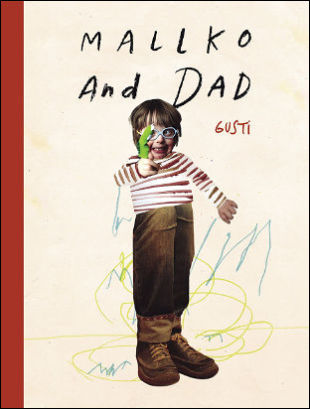

Strictly speaking, Mallko and Dad is not a children's book. But then very little about author Gusti's experience as a dad followed what he expected, so why should this book fit into a pigeonhole? Like Gusti and his wife Anne's young son Mallko, this book is fully original.

When Mallko was born with Down's Syndrome, Gusti's first reaction was "I did not accept him." He felt this sentiment so strongly that he writes it out in bold capital letters on an expanse of two pages. He compares this difficulty with the problems he has as an artist when he rejects some of his drawings as being no good. Gradually, though, he realizes that like his discarded drawings, Mallko is complete.

With lavish and entertaining mixed-media illustrations which range from photos to collages to cartoons, Gusti goes on to give us a journal-style view of this completeness. He starts by sharing other family members' responses to Mallko. For instance, when Mallko's older brother Theo, aged eight, learns what Down's Syndrome is, he proclaims: "I don't care if he's green, red, blue, silver, hairy, or short and fat. He's always going to be my best little brother." Gusti says that in that moment he "looked at Theo and saw an enlightened master."

While Gusti gives us the gift of seeing Mallko in a wide range of moods and modes, the one that comes through most clearly is play. A sheet of paper with two long triangles on it becomes a mask that makes Mallko into a vampire, not that vampires ordinarily burst out laughing. He puts on a cap and takes off a cap over and over again to the tune of La cucaracha.

Every time Mallko goes out for a walk with his dad, he zooms off and refuses to hold hands. Here, like in so many places in the book, Gusti's observations are astonishingly honest. He has to figured out what to do with a runaway Mallko and eventually picks up his son, announcing (in successive cartoon frames) "I can't see" and "Mallko, you're choking me" as Mallko tries to hold on. Those who spend time with children will know this exact sensation.

Gusti is equally honest about the changes in his perspective. As someone who formerly was a "radical proponent of homeopathy and natural remedies," he comes "to see the good side of mainstream medicine," for along with Down's Syndrome comes a host of health challenges.

Gusti allows himself to be as playful with the illustrations as he is with this new life experience. Sometimes his drawings are rudimentary, like something a first grader would draw. And then we come across breathtaking beautiful spreads, like the one with twelve different pictures showing Mallko's endless love of chasing pigeons. His joy in freedom of movement could not be more contagious.

Gusti was born in Argentina and wrote this book while living in Barcelona, so the pages are sprinkled with Spanish as well as English, much of it handwritten and often reflecting the extraordinary support and understanding of family friends. This book's depth and variety needs to be seen to be fully appreciated, but you can grasp its essence from the song lyrics on a page near the end:

"The stars have the mark of God.

Goodness has the mark of God.

Freedom has the mark of God.

Hope has the mark of God.

Sadness has the mark of God.

Music has the mark of God.

Your brother has the mark of God.

Nature has the mark of God.

Children have the mark of God.

Your son has the mark of God."

A young child might enjoy looking at the pictures in this book with some guidance from someone older. An older sibling of a Down's Syndrome child could greatly benefit from its wisdom. Most of all, we think the book helps grown-ups who need reminders that " 'Accepting' is willingly and gladly receiving what we've been offered." Gusti himself has come so far along this road that he co-founded the nonprofit association Windown-La Ventana, which works toward building a more inclusive society.