The Wabanaki people — whose lands once included present-day Maine, parts of Quebec, and Canada's Maritime Provinces — have been harvesting sweetgrass for thousands of years. Suzanne Greenlaw and Gabriel Frey write in an author's note accompanying this book that "the sweetly scented, emerald-green grass holds spiritual, economic, and cultural importance for the Wabanaki and many other First Nations across the continent."

In this story, a contemporary Wabanaki girl and her grandmother drive to a salt marsh to harvest sweetgrass "where the river meets the ocean." It's the girl's first experience of harvesting, and the grandmother tells her that her own grandmother used to bring her here also to pick sweetgrass for weaving into baskets. "We call it welimahaskil, and we use it in ceremony as well as baskets. Sweetgrass is a spiritual medicine for us."

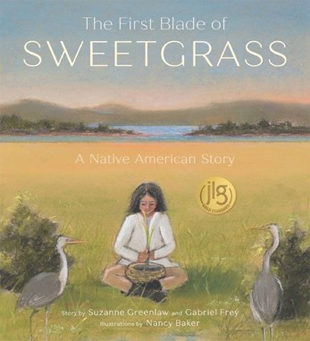

Maine artist Nancy Baker gives us peaceful, majestic vistas of these sacred meadows along with views into the grandmother's memories: for instance, indigenous women burning sweetgrass in a smudging ceremony at a fire circle. She conveys the grandmother's tender watchfulness as she guides her granddaughter toward distinguishing sweetgrass from the other grasses. "Sweetgrass has a shiny green tassel and blades and a purple stem, and it gives itself to you," Grandmother says. "If you tug lightly on a piece of sweetgrass, it will let go. If you have to pull hard, you are not pulling sweetgrass."

But the most important wisdom she conveys is "we never pick the first blade of sweetgrass we see." Leaving that first blade intact ensures that the sweetgrass will never be depleted, that there will be sweetgrass for the next generation. Even through her difficulties identifying sweetgrass on her own, the girl remembers this advice and, when she does discover sweetgrass, she takes care not to pick the first blade.

Such gentle wisdom about stewardship, known and followed since ancient times by indigenous people, has the power to reverse the devastation that Earth currently experiences due to human disrespect and greed. As the girl plans to return next summer and teach her younger sister how to pick sweetgrass, readers ages six to eight understand that she would be passing along not merely a skill, but also a vital, restorative way of relating to nature. This respectful relationship is one that they, too, can emulate.

In addition to the insightful authors' note at the end, readers will find a glossary of Passamaquoddy Maliseet words used in the story and a link to a full dictionary where they can translate to and from English and hear these words spoken. One of the glossary words is Kuli-kiseht: Good job. It surely fits this book's ability to draw us closer to the reverent perspective we have always needed to take — and never more so than now.