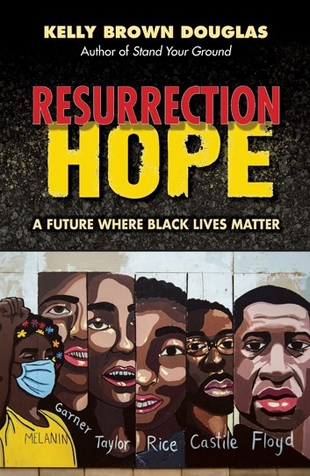

We were finally ushered into a new age on the day of the tragic and appalling murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020. Consciences were raised, at least for a time, in ways that might lead to real and lasting change.

Kelly Brown Douglas, Canon Theologian at Washington National Cathedral and dean of the Episcopal seminary in New York City, walks readers through the terrain of historical anti-blackness, white privilege, and the devaluing of Black bodies. That’s chapters 1 and 2.

Chapter 3 is where she cuts to the heart of the dominant white Christian ethic of love of God and others and how it is built on blind prejudice, racism, and misunderstandings of the Gospel. She begins by questioning, “Where were the white Christian voices,” before May 2020, “as the virus of white supremacist anti-Black injustice disproportionately trapped Black lives in the crucifying realities of poverty?”

Soberly, she adds: “Just as white supremacy has not disappeared, neither has the religion that fosters and legitimates it,” because many Christians have adapted what were once overt pro-slavery attitudes into “twenty-first-century cultural mores and political sensibilities,” such as the whole “Make America Great Again” vision of Trump and his allies.

Douglas says to “good white Christians” who offer that they are praying for change or are praying for Black people in these times of trouble: “Jesus was nailed to the cross because he protested the oppressive political, social, cultural, and religious systems and structures of his day, even as he bore witness to God’s promised just future…. That he did not resist his crucifixion reveals his solidarity with the subjugated, dominated, marginalized classes of people of his day in their struggle for life and freedom.”

She encourages would-be good white Christians, who say that they follow Jesus as Lord, to do more than pray — to no longer be passive or tepid when it comes to injustice.

Black visionaries from sociologist W. E. B. DuBois, who wrote The Souls of Black Folk in 1903, to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., to novelists James Baldwin and Toni Morrison, to Bishop Michael Curry, current Presiding Bishop of The Episcopal Church USA, are quoted throughout the book. News accounts and political commentators are also referenced – much more, in fact, than theologians or spiritual writers.

Chapter 4, “Resurrecting Reparations,” is already sparking a great deal of discussion and introspection. Religious groups may, and sometimes are, leading the way.

Then the final chapter, “Resurrecting Testimony,” advocates what might surprise readers, laughter: “To laugh is a signal of transcendence. It is that which signals a discrepancy between what is and what ought to be, the discrepancy between our unjust present and God’s just justice.” This is the laughter of a prophet, an expression of the “Resurrection Hope” of the book’s title.