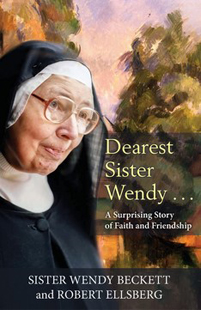

I hope you haven’t forgotten Sister Wendy Beckett. A quarter century ago, she was widely appreciated throughout the English-speaking world for her insight, wisdom, and wit on television talking about visual art. An awkward, introverted, and contemplative nun, she was brilliant.

Look her up on YouTube if you don’t believe me. She once wrote, “Art, like prayer, is always the expression of longing”—and endeavored to show, even in the most obscure works of modern art, how longings of human beings are expressed and help us understand who we are and who God might be.

We have more than a dozen reviews of Sister Wendy’s writings about paintings and other forms of visual art, for example, this review of her book on the mystery of love in art.

Book publisher and author Robert Ellsberg (also a mainstay on our site, author of important books on saints, Dorothy Day, and other topics) knew the art historian and religious Carmelite well and carried on a long and meaningful correspondence with her. This book offers the opportunity to look-in on what they had to say to each other over a very intense two-and-half-year period.

A variety of characters familiar to those who frequent Spirituality & Practice appear here, too. Adding to the appeal, some of their photographs are in the pages as well. For example, when Ellsberg mentions in a letter that he’s just had a visit with Jim Forest, “my oldest friend, and now my author,” Sister Wendy writes back to say: “How sustaining it must be to have a friend like Jim. When I was 14 and met Val I realized with almost incredulous happiness that God had given me a friend, knowing as I did that as soon as I was 16 I would be entering religious life, where I thought at that time the absoluteness of God’s love expressed in the vow of chastity ruled out friendships.” One pleasure in these pages is watching Sister Wendy process her religious formation years and principles with who she has become as an older adult contemplative. At times the transformation is subtle; at other times, it’s intense.

Thomas Merton appears here, as well, in the conversation between the two letter-writers and in a photograph. Ellsberg seems ready to excuse and explain Merton’s well-known love affair with a woman, in violation of his monastic vows, whereas Sister Wendy takes Merton to task. Still, a change takes place over time, we see, watching Beckett gradually come to forgive the famous monk: “I’ve often been grieved that Merton never seems contrite about his extraordinary breaches of the rule … [but] I see that I am too narrow in categorizing him, and understanding this makes me feel very much less grieved, because he is a wonderful man and has influenced so many, as you say.”

Sister Helen Prejean, of Dead Man Walking fame, appears here. So do Thich Nhat Hanh, Julian of Norwich, Henri Nouwen, Daniel Berrigan, Joan Chittister, and others, all in photographs. We also get to see Sister Wendy and her sisters and some of the paintings and icons that so moved her, which she sometimes sent as reproductions to Ellsberg along with letters.

There are beautiful moments and sentences. Sister Wendy, for example: “I can’t think God minds our mistakes as long as we make them looking at Him.” Also: “As long as we think that happiness depends upon everything going well with us, we are living in a state of illusion.”

Ellsberg is often prompting the nun to think about contemporary issues that one imagines she wouldn’t have otherwise faced, living as a consecrated hermit. There’s even an occasion when he prods her regarding gender fluidity, using the example of the early sixteenth century Spanish Franciscan mystic, Juana de la Cruz Vázquez y Gutiérrez, whose cause for canonization has received attention recently from Pope Francis.

One of the great surprises is how Ellsberg’s attention to dream interpretation over time prompts Sister Wendy to dream and talk about her own dreams more intensely. See the excerpt accompanying this review for a beautiful example of this.