Nevada Barr is the award-winning author of eleven Anna Pigeon mysteries, including the New York Times bestsellers Flashback, Hunting Season, and Blood Lure. She lives in Mississippi, where most recently she was a ranger on the Natchez Trace Parkway. In her nonfiction debut, Barr charts her spiritual quest as she moves slowly from atheism toward a more loving acceptance of herself, others, and God.

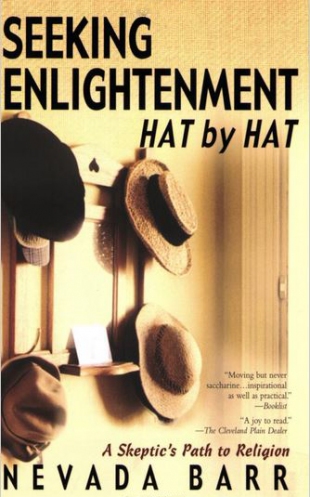

The title refers to the author's love of fine hats and the fact that she is the only one in the Episcopal church she has been attending for six years who regularly wears one: "My hats, with their feathers and veils and dusty velvet, remind me that there are times in life when it is important to pay homage and respect, when it behooves me to wash my face and hands and put on my Sunday best." This habit reveals Barr's spunky style that makes her account of spiritual rehabilitation a delight to read. Those who have enjoyed Annie Lamott's writing on religious matters will find the same panache and honesty in this seeker's journey.

After hitting bottom at age 41 with a divorce and clinical depression, Barr decides to chuck her sturdy skepticism about God and religion. She begins to do some detective work: "I will keep my eye out for Him in the neighborhood, try to be ever vigilant, assuming that everyone from the pizza delivery girl to the guy with the obnoxious all-terrain vehicle could be him, or at least of him. I will cultivate blessings and grace in the dirt of my garden, the words of my friends, the eyes of my dogs." Barr offers her own spiffy definitions of religious terms. Sin is "really rotten ideas"; turning the other cheek is an act of courage that involves taking in pain and containing it; humility is letting go of "inflated visions of Me"; and telling the truth is a way of feeling comfortable in one's skin.

In an inspired passage, the author reminisces about Halloween as a special time when children were once free to explore the dark on their own, meet their demons, experience power, and rely upon the kindness of others. But now adult fears have curbed this ritual. This says quite a lot about Barr's spiritual maturity and her respect for the essential role of the shadow in the lives of young and old alike.

It would be fun to sit next to her at a congregational get-together in Mississippi. Perhaps she would lean over and whisper the words that appear near the end of this satisfying book: "Community is God rubbing elbows and passing the tuna casserole, a place we can snuggle down with the divine."