"I cannot taste a cup of water but I recall that the eye of the lake is my grandfather's, and that the lake's heavy, blind, encumbering waters composed my mother's limbs and weighed her garments and stopped her breath and stopped her sight. There is remembrance, and communion, altogether human and unhallowed. For families will not be broken. Curse and expel them, send their children wandering, drown them in floods and fires, and old women will make songs out of all these sorrows and sit on porches and sing them on mild evenings. Every sorrow suggests a thousand songs, and every song recalls a thousand sorrows, and so they are infinite in number, and all the same." So writes Marilynne Robinson in her masterful debut novel.

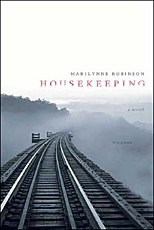

There are certain novels in which the author is able to gracefully weave form and content together into one well-crafted and thematically allusive work of art. Such is the case with Housekeeping. Time, nature, and the supreme mystery of the human personality are fluidly presented in this tale set in Fingerbone, a town "chastened by an outsized landscape and extravagant weather, and chastened again by an awareness that the whole of human history has occurred elsewhere."

Young Ruth, the narrator, and her sister Lucille are left with their grandmother just before their mother commits suicide. Lily and Nona, two maiden great-aunts, take over the chore of raising them. Finally, Sylvie, the vagabond sister of the girls' mother, arrives to serve as their caretaker.

"We had really never had any use for friends or conventional amusements. We had spent our lives watching and listening with the constant sharp attention of children lost in the dark," notes Ruth. Sylvie is a transient in her bones, sleeping with her clothes on, chatting with strangers in the train or bus station, wandering by the lake and returning with fish in her pockets, savoring evening as her special time of the day, cherishing "the life of perished things." Ruth is intrigued but Lucille rebels against Sylvie's unorthodox lifestyle and attitudes.

Ruth muses: "If I had my particular complaint, it was that my life seemed composed entirely of expectation. I expected — an arrival, an explanation, an apology . . . That most moments were substantially the same did not detract at all from the possibility that the next moment might be utterly different. And so the ordinary demanded unblinking attention." Ruth and Sylvie spin out their days in a reverie of trips and inward excursions while the townsfolk fret about them. And when they leave together, the reader realizes that Ruth has found a niche as a wanderer with her own special calling to watch, wait, and listen for surprises that await her just around the next bend.