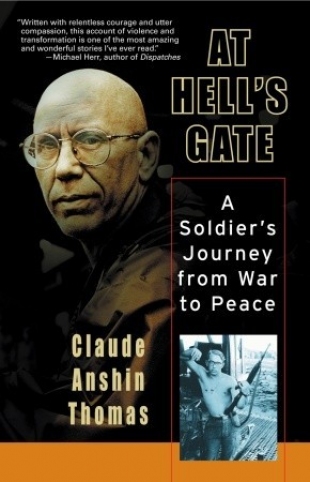

Claude Anshin Thomas was physically abused as a child by both of his parents. The seeds of violence were watered in him as an adolescent growing up in America. He volunteered to fight in Vietnam at 18 and served as crew chief on assault helicopters. During his time there, he killed hundreds of people. At the end of his tour of duty, Thomas was awarded numerous medals, including the Purple Heart. Back in America, like many other veterans of that war, he had to fight post-traumatic stress, drug and alcohol addiction, and feelings of self-hate and isolation.

Thomas's life was turned around by attending a meditation retreat for Vietnam veterans led by the Zen Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh in France. Here he learned about the healing powers of meditation and mindfulness which enabled him to face his overwhelming feelings of guilt, anger, and sorrow rather than continuing to try to escape them. Eventually ordained as a Zen monk and teacher by Bernie Glassman, founder of the Zen Peacemaker Order; Thomas chose to live as a wandering mendicant monk. He took vows not to work in the conventional sense and not to accumulate possessions. He now travels throughout the world for 260-265 days per year, living a period of each year on pilgrimage, studying, accepting invitations to teach meditation, and living homeless on the street.

A respected spokesperson for nonviolence, Thomas has promoted peace in war-scarred places around the world including Bosnia, Afghanistan, Vietnam, and the Middle East. He writes about a turning point in his life: 'An important moment for me was seeing the execution wall at Auschwitz. I walked up to this wall and faced it, and then I turned my back to it. I spent some time standing there, seeing myself as one of those who faced execution. Then I walked forward, turned, and stood where the executioners stood, to see myself as one of them. Because in reality I am both. In war there is no separation. It is true that the Nazis and the Jews were different, but I must also see how they are not different, how each of us has the potential to become both the persecutor and the victim."

It is this Buddhist practice of compassion that forms the backbone of his nonviolence: "I also know that the commitment to nonviolence requires an almost complete overhaul of our conditioned nature. It requires us to live differently and demands great courage and great sacrifice. Ultimately, all responsibility and all action begin with the individual, and so it is here that we must start. In its simplest form, nonviolence is rooted in the knowledge that we have the capacity to act violently and aggressively and that we make a conscious choice not to. Nonviolence is not succumbing to our conditioning, not succumbing to our sense of helplessness that has us deciding again and again, either actively or passively, to support the use of violence as an effective form of conflict resolution. Nonviolence means strongly standing up for truth and compassion in the midst of confrontation — and doing so without aggression."

This gripping spiritual memoir bears witness to the transforming power of meditation and mindfulness in the life of a Vietnam veteran. His generous and committed presence in the world as a peacemaker gives us all hope to carry on in our own small efforts to practice nonviolence as best we can.