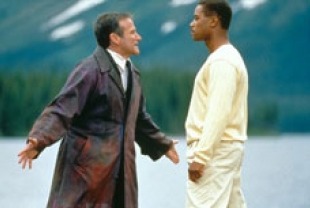

This spiritual adventure film, with a screenplay by Ron Bass based on a book by Richard Matheson, boldly begins with the idea that eternity is similar to the realm of the imagination. Chris (Robin Williams), a pediatrician, and Annie (Annabella Sciorra), a painter, are soul mates whose love relationship seems invincible. However, when their two children (Jessica Brooks Grant and Josh Paddock) are killed in an automobile accident, Annie has a breakdown and is institutionalized. Chris pulls her back to reality but then he dies while trying to help others at the scene of a terrible wreck. He ends up in Heaven where he is escorted around by Albert (Cuba Gooding, Jr.) and Leona (Rosalind Chao), who both know a lot about his past.

This is an oddly American version of the afterlife as totally individualistic. Chris finds himself wandering around inside one of Annie's impressionistic paintings of the place where they met and planned to grow old together. Albert and Leona have private Heavens, too, that are consistent with their memories. God is nowhere to be found, a view that is contrary to the rich tradition of Heaven as a place of union with the Creator put forth by Western religions.

This afterlife reflects the idea that "belief creates experience" or "thinking makes it so" common in today's pop psychology circles. To move through the heavenly realm, all Chris needs to do is see those desired images. This may seem strange to rationalists, but such movement will be quite familiar to those who have practiced waking dreams, lucid dreaming, shamanistic traveling, and other experiences in the imaginary realm. Still, the film's simplistic credo — "Thought is real; the physical is an illusion" — does a disservice to the spiritual depths of the imagination as a separate reality.

The special effects, however, are striking and provocative. Vincent Ward (The Navigator, Map of the Human Heart) is the perfect director for this kind of visually rich presentation. The scenes of flying people outside a Heavenly City, shipwrecks at the gates of Hell, and a surrealistic sea of faces of lost souls are arresting and thought provoking.

As interesting as these visions of Heaven and Hell are, the film is best when it is addressing a different subject altogether: How do we reach someone who is in deep despair? Chris must find an answer on two occasions: trying to reach a self-blaming and very withdrawn Annie at the mental hospital and, later, communicating to her through her denial of him in Hell. His strategy on both occasions is the same. He realizes he has failed her not because he couldn't change her or be stronger for her but because he couldn't join her. When he does — when he suffers with her — their soulmate bond is reaffirmed. Starting out as an exploration of the imagination, the film ends with an eloquent statement about compassion.