I Am Not Your Negro, having screened at the Toronto and New York Film Festivals, opened on December 9 for a special one-week advance preview at Maysles Cinema and Metrograph in New York and Cinemark Baldwin Hills in Los Angeles. It will then be released to theaters in 25 markets on February 3, 2017. It will also be available at that time through Amazon streaming.

Although Raoul Peck's substantive and immensely insightful documentary focuses much of its energy on the fights for racial and economic justice during the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, it has much to say about the uneasy and troubling signs of racial hatred afoot in our times. At the hub of this mind expanding film is the author, essayist, and political activist James Baldwin.

The filmmaker decided to make every word in this documentary one from this articulate African-American author's essays, letters, and Hollywood film commentaries. For a while, Baldwin lived in London and Paris as an expatriate seeking to both escape from racism in his homeland and to see it afresh from living abroad. He laments that the U.S. remains "a complex country that insists on being very narrow-minded." And this refusal by Americans to open their hearts and minds to radical pluralism has led to the "apathy and ignorance" which are the "price of segregation." Samuel L. Jackson does an exceptional job with his nuanced shadings of the varied voiceovers.

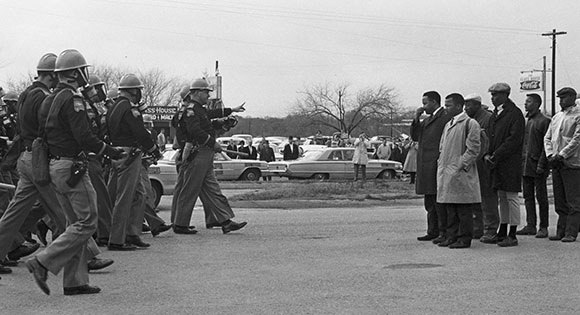

Just before his death in 1987, Baldwin told his agent that he was going to write a book called Remember This House, a bold and ambitious attempt to deal with the civil rights activities and successive assassinations of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr. He only completed about 30 pages of this book; this documentary attempts to show what else he would have said. It conveys the hatred, violence, and prejudice which these black men faced in their different leadership roles. It also uses archival footage of the Civil Rights movement as a bridge to the racial flare-ups of our times and the response of the #BlackLivesMatter movement. Police in both eras use excessive violence on unarmed black men, women, and children.

One of the most telling elements of this production is the use of Baldwin's commentaries on Hollywood movies. Clips illustrate the impact of racism on popular culture in The Defiant Ones; Imitation of Life, King Kong, Dance, Fool, Dance; and Guess Who's Coming to Dinner?

Raoul Peck's sober-minded documentary stands alongside Ava DuVernay's 13th as two prophetic challenges to white America to set sail on a new course of peace, reconciliation, and forgiveness. Or as Baldwin has written in an essay entitled "Down at the Cross":

"The white man is himself in sore need of new standards, which will . . . place him once again in fruitful communion with the depths of his own being. . . . The price of liberation of the white people is the liberation of the blacks — the total liberation, in the cities, in the towns, before the law, and in the mind."

More Quotes from James Baldwin

The lasting legacy of James Baldwin is his unflinching ability to cut through and demolish the veneer of rectitude that conceals the toxic reality of the oppression of African-Americans in the United States. It is not easy to take a stand and oppose the warps of society, knowing that these actions may well lead to persecution and constant attack. Armed with a flinty courage, Baldwin wrote in Notes of Native Son:

"I love America more than any other country in the world and, exactly for this reason I insist on the right to criticize her."

Witnessing the racial hatred of the police and others who beat and kicked the bodies of blacks and other nonviolent Civil Rights marchers in the South and elsewhere, we ask why and recall Baldwin's observation in The Fire Next Time:

"I imagine one of the reasons people cling to their hates so stubbornly is because they sense, once hate is gone, they will be forced to deal with pain."

During his long and mostly illustrious writing career, Baldwin had enormous influence on the literary and intellectual history of his times. The media provided him with plenty of opportunities to comment on what it was like to be a black man. Here is one answer given in The Fire Next Time:

"You were born into a society which spelled out with brutal clarity, and in as many ways as possible, that you were a worthless human being."

And in an interview for The New Negro, the essayist and novelist went even further:

"To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time."

It takes time and effort to cool the down the heat of rage. But those who listened to the words and were inspired by the compassion and forgiveness of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., were challenged to incarnate charity in the presence of enemies. Baldwin wrote about this in The Fire Next Time:

"It demands great spiritual resilience not to hate the hater whose foot is on your neck, and an even greater miracle of perception and charity not to teach your child to hate."

Baldwin, as we have seen, refused to allow himself to be locked up the ideas or descriptions provided by racists or other closed-minded bigots. This stance resulted in both a positive and a negative outcome as he stated in A Talk with Teachers:

"Precisely at the point when you begin to develop a conscience you must find yourself at war with society."

In his foreword to James Baldwin: The Legacy, Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka celebrates this author's lovingkindness by imagining him in a special place acting in beauty and truth:

" 'If I hurt you, I also hurt myself.' At the Welcome Table in the Great Beyond, I have no doubt that we shall find Jimmy seated between some Grand Master of the K.K.K., Governor Wallace and the Scottsboro boys, enjoying a wise laugh at the former's unease, applying to their self-inflicted wounds the soothing balm of his imperishable, celestial prose."