Aretha Franklin barely speaks a word during the running time of Amazing Grace, the finally released concert documentary of her 1972 two-night appearance at Watts’ New Temple Missionary Baptist Church. But her superlative singing and the occasional close-up on her forever focused face speak volumes about this astonishing artist’s talent and faith. Franklin proves, song after song, that an artist of her caliber has the potential to ignite hearts and minds with uncommon prophetic power.

Filmed when the Queen of Soul was just on the cusp of turning 30 and capturing her voice and presence in raw, top-notch form, Amazing Gracehas been lost to history for nearly half a century. Though the sound recording of these live sessions comprises Franklin’s best-selling album, the film itself, with its out-of-sync audio glitches botched by the then-young director Sydney Pollack, was rendered unreleasable for decades. But music producer Alan Elliott has now matched the picture and sound as closely as possible, and this performance for the ages is now available to shake the rafters and stir the soul.

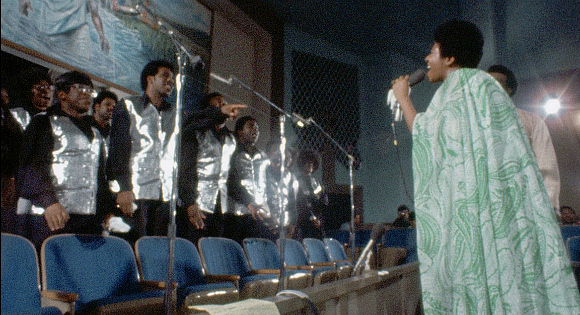

As with most sonic spiritual experiences, it is best to simply allow the music and majesty of Franklin’s performance to wash over the viewer (and listener). She is accompanied by Reverend James Cleveland and the Southern California Community Choir, and bolstered by a proud mid-concert sermon by her father Reverend C. L. Franklin and shots of rapturous, attentive audience members. The film is more an electric church service, a sacred revival, than it is an informative documentary. It reveals no new information about the artist herself, yet it invites the audience into a relationship that feels deeper than information-sharing or even storytelling; it creates ritual and reminds the willing that there is meaning beyond what can be expressed in words.

The fact that this chronicle has been lost for so long only adds to its current potency. Watching it and listening to it (for it feels like these two things become one sense while in the grip of Franklin’s performance) conjures a specific time and place, a specific culture and people, while also agilely speaking to a universal human desire to encounter the divine, to praise the Universe with joyful shouts and quiet hums, and to seek new horizons of communal potential. Franklin and her collaborators created something for a relatively small audience over those two nights, with the thought that it might reach a broader audience eventually, but the fact that this broader audience is only seeing it now, decades later, heightens the entire enterprise to mythological proportions. It truly feels monumental, even as it never once loses its very touchingly human quality.

Without ever making overt political statements or proffering a specific point of view, Amazing Grace still packs a punch that needles the soul. In its current state, the film is content to allow Franklin’s performance itself and the story of its wandering path to release to combine in a kinetic celebration of Gospel music, the Black church, the resurrection of a long-lost moment, and the unshakable faith of a people. It rises as a testament to Franklin’s devotion to her roots, to her calling, and to her hopes for a future fueled by faith, sustained by community, and led by voices that refuse to be silenced.