Director Claire Denis seems to love leaving things out. Her films often feel like nightmares, trippy terrors in which leaps in time and space go unexplained, pieces feel scattered or missing, and characters surprise with their rash choices and mystifying moves. She is more a dreamweaver than a storyteller, more a spinner of befuddling prophetic visions than a clear communicator. She has always seemed like a mystical tour guide of realms beyond our human imaginations, so it seems natural that, with her latest creation, High Life, she would finally find herself actually lost in space.

At the center of Denis’ first-time approach to genre cinema are the makings of a conventional sci-fi thriller. A ship has been launched into space carrying a motley cohort of convicts. They appear to be on a suicide mission, inching toward a black hole whose mysterious depths just might hold the answer to saving the suffering planet they’ve all left behind. But, with these facts established, it soon becomes obvious that this is no traditional astronauts-and-aliens fare, but rather a slow-as-molasses meditation on space, time, connection, loneliness, loss, and, ultimately, hope. Denis doesn’t always steer her tales toward that latter, sunnier theme, but even though this film’s ending is as elliptically eerie as any of her earlier work, there is also a strange, melancholic faith that breaks in and sheds an unexpectedly lovely light.

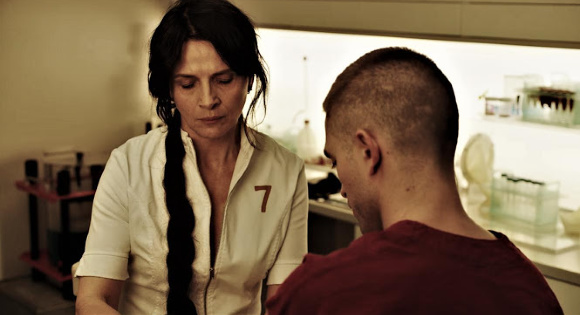

With such free-floating storytelling, it might be easy for performances to get lost in the nonlinearity of it all, but Denis has populated her ship with fine ones, most especially from Robert Pattinson and Juliette Binoche, who both craft intriguing characters, even out of what amounts to a series of evocative but sketchy scenes. Pattinson’s Monte, a quiet and withdrawn Death Row inmate, juxtaposes with Binoche’s Dr. Dibs, another criminal with a truly unsavory past and a truly unsavory mission of her own. In short, Dr. Dibs wants to extract semen from the male passengers and impregnate one of the female passengers, and Monte is the one man who consistently eludes her overtures. And as the black hole comes nearer, her beguiling need to create something before they are all obliterated takes on a manic, mesmerizing meaning, begging a queer question that moves beyond mere sci-fi fodder and into more expansive existentialism: Destruction and death are certain, so why bother making new life?

Denis doesn’t so much ask this question as she plants the seeds for her characters to pursue carnal answers to it. She’s not interested in her film spoonfeeding morality. Instead, she wants the beastly behavior of the humans onscreen to activate the audience’s imagination. Strange sexual proclivities, bursts of violence, and even quiet escapes into gardening showcase the unique approaches that desperate people take in order to maintain or regain sanity in close quarters. Denis’ hazy, dreamlike approach coyly invites the audience to imagine just how they would act were they trapped in the same closed-off space. This is not straightforward filmmaking; it is filmmaking as spiritual disruption, demanding that viewers go on a journey that feels maddeningly mystic, asking them to give in to their confusion and not seek easy guideposts.

Scenes from when the ship was more populated are intercut with more desolate, later times, in which Monte is now raising a young girl, named Willow (Scarlett Lindsey). How Willow has been conceived is a disturbing revelation, but the father-daughter relationship is tough and tender, tentative and caring, and their loving bond evolves in stark contrast to the brutal scenes with Monte’s original crew. How these two have come to be alone on this claustrophobic capsule is somewhat explained and somewhat vague. Denis shows the ends that befall some, but keeps just enough left out that no explanation ever feels completely solid. The plot holes end up feeling like black holes themselves, ones that suck the air out of narrative propulsion, but which also create new possibilities for imaginative narrative reconstruction in their place.

High Life’s narrative slipperiness ends up feeling less like lazy filmmaking and more like an intentionally cryptic dispatch from an uncertain future. Denis has taken her ability to represent domestic discord in prior films and launched it into a stratosphere that feels both frighteningly fated and oddly auspicious. As in all of her work, salvation will come with a terrifying price, but High Life’s strangely resurrective final moments suggest that Denis’ apocalyptic visions for the end times might just hold more hope than horror.