No words are needed to bring home the message of Victor Kossakovsky’s Gunda. Beautifully shot in black and white, the vibrant personalities whose mundane daily lives fill the entirety of this quietly shattering film don’t speak. They simply grunt, moo, and cluck, speaking mysterious languages untranslatable for any human. Lovingly following the lives of a family of pigs, a gaggle of chickens, and a herd of cows, Kossakovsky dares to feature the babble of this barnyard community without the typical commentary familiar in nature documentaries. The result is an uncommonly spiritual and life-altering experience.

The lack of verbal guidance invites viewers to observe without receiving anthropocentric context, allowing the animals to represent themselves. It’s a daring move, especially in an age of increasingly short attention spans, and it’s not the only challenge that Kossakovsky makes. He also wants his audience to wake up to these lives that we humans too often take for granted. He wants us to encounter the lives we literally devour by the billions every year. And yes, he wants us to change our ways for good.

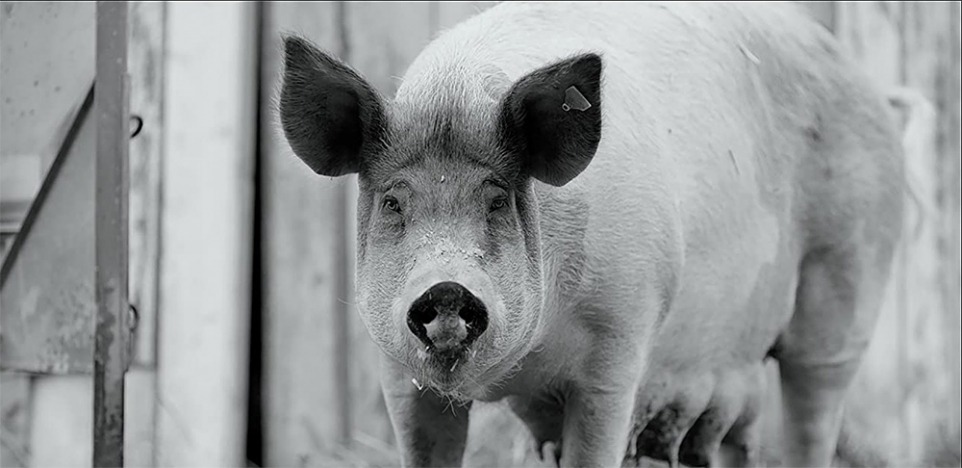

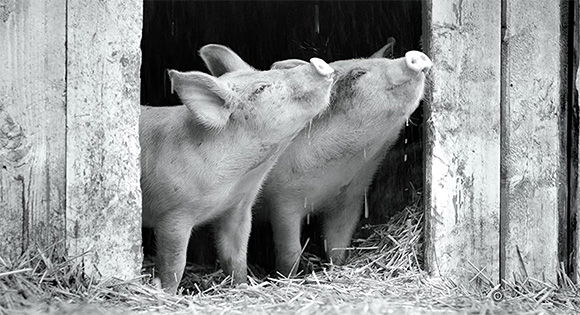

Over half of the film’s 90-minute running time is dedicated to the titular character herself. A meaty sow with a deeply soulful gaze, Gunda is first encountered lying alone in a ramshackle hut. After a few moments, a freshly-born piglet appears, then another, and another, until Gunda is surrounded by a just-arrived family, all of them ready to eat. From there, Kossakovsky’s camera unobtrusively records Gunda’s children as they age, continuing to eat, digging in the ground, covering themselves in mud, growing from tiny newborns to spunky adolescents who can’t even comfortably fit next to one another as they feed at Gunda’s teats.

Interspersed with this porcine narrative are subplots featuring the charming chickens and laidback cows who also live on the land. Moving at a glacial pace, Kossakovsky subtly builds connections between the intersecting lives of these creatures whose individual lives are rarely featured with such care, focusing on their undeniable sentient grace. The meandering style might easily lull most viewers into a glazed-over meditative trance, but Kossakovsky peppers the long stretches of banality with purely breathtaking moments. A close-up shot on a chicken’s foot, footage of piglets delighting in the taste of raindrops, a cow’s face covered in dozens of gnats, these seemingly quotidien images become sacred glimpses into the ultimate mystery of existence itself.

Kossakovsky’s ultimate goal is to gently force his audience to question their own dismissal of these remarkable creatures, but Gunda is not simply a piece of animal rights propaganda. Gunda features no terrifying trips to a slaughterhouse, but the invasive human violence inferred in its final moments is as chillingly effective as any gory footage of actual butchery. Instead of relying on jolting shock and honed argument, Kossakovsky relies on the faces of his characters to conjure the undeniable beauty of their lives and the undeniable cruelty of how hungry humans ceaselessly intrude upon those lives.

And the faces, especially Gunda’s, are what linger long after Gunda ends. Noticing those eyes filled with curiosity and wonder, brows inquisitively furrowed, noses and beaks anxiously twitching, mouths open in exclamation and protest, sounds both friendly and furious drifting into the vastness of the surrounding ecosystem, it is both impossible to know what is going on in the minds of these amazing beings and impossible to ignore the fact that there is definitely something miraculous going on.

Whether or not a trip to Gunda’s farm will ultimately convince all human tourists to examine their diets and anthropometric assumptions, Kossakovsky has crafted a sacred text to be excavated, absorbed, and respected as an invitation to repentance. It has taken centuries for some privileged people to even begin to recognize the humanity of their fellow humans, and there is still a long way to go. Alongside this slow progress of human rights recognition, many humans have, for millennia, placed themselves at the center of the universe and at the top of the food chain.

We are seeing the power of living into equality and interdependence among humans. So now, what further insights into ourselves and our future might an authentic decentering of the human experience compel? Gunda and her companions on the farm might not have the language to answer such a question for us, but we humans do, and the continuing development of our own humanity rests on our willingness to find new ways to better participate in a world that is far larger than our presumptuous attachments to deadly dominion.