"I'm just so upset about the beheadings. How can people just go about their business when this kind of thing is happening?" The question came up during a phone call in September. The next week we went to see the "Eyes Wide Open" exhibition in the meeting room of our church in New York City, and we wondered how people could ignore the deaths in Iraq. The exhibition consisted of more than 1,000 pairs of boots arranged in neat rows to represent American soldiers killed in Iraq. Off to the side were more boots plus children's shoes, sandals, sneakers, and high heels representing Iraqi civilians killed in the war. Now we learn that research from Johns Hopkins University indicates that 100,000 civilians, most of them women and children, have died as a result of the Iraq war. We couldn't fit that many pairs of shoes in the whole church building.

Why isn't this human cost of war getting more attention? Perhaps because many of us just don't want to know about it. Our culture fears death and tries to keep it out of sight. No flag-draped coffins show up on the evening news. We're fascinated by violence and fill our entertainments with it, but real death, the end of life — that we don't want to deal with.

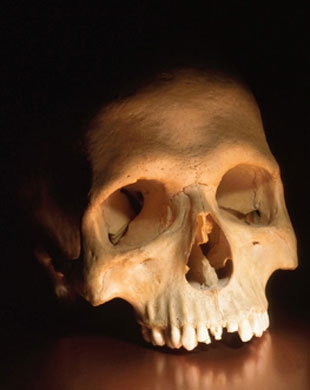

In contrast, teachers from all the religious traditions recommend that we face death and even befriend it. Saint Benedict tells us to keep death daily before our eyes. Medieval philosophers kept a skull on their desks to remind them of the impermanence of life. Rabbi Harold Kushner interprets poet Wallace Stevens' comment "Death is the mother of beauty" to mean that we cherish and find things beautiful precisely because we know they will not be around forever nor will we always be here to enjoy them. Death, in other words, brings meaning to life.

We've collected some readings that examine attitudes toward death in our culture and in some of the religious traditions. Suggested practices give you opportunities to live with death. We recommend you include some of them in your traditional observances of All Soul's Day, All Saint's Day, Halloween, and the Day of the Dead.

Book Excerpts

Book Excerpts

- Michael Lesy on Death as the Forbidden Zone

American historian Michael Lesy describes the forbidden zone that every citizen knows but fears to enter. "Most of us want to know only just enough to experience it imaginatively and then live to tell the tale, like Lazarus returned to the light." So we hide evidence of real death and instead read about pathological killers, fill our entertainment with fictional deaths, and line up for violent movies. People used to die at home and their friends prepared the bodies for burial; cemeteries were places to contemplate the dead. "Ordinary and inevitable death has become so rare that when it occurs among us it reverberates like a handclap in an empty auditorium." He tells the story in John O'Hara's "Appointment in Samarra" when Death accidentally jostles a man in the bazaar in Baghdad, who runs away in fear to Samarra, thinking he can avoid that appointment. "Like that man, we try to avoid the inevitable, and so our lives are awash with it."

- John R. Aurelio on Taking Death in Small Doses

We flee death by changing the subject, not listening when it is brought up, or cosmetizing it. We don't help children deal realistically or effectively with death, and we don't do so ourselves. Aurelio, a Catholic priest, suggests ways to take small doses of death to build up our resistance. This is not avoidance but rehearsing.

- Marie de Hennezel on How Death Teaches about Aliveness

Hospice worker Marie de Hennezel laments that we hide death, treating it as if it were shameful and dirty, a scandal even, rather than as life's crowning moment. She talks about what she has learned from accompanying people through the living of their final moments: "My own sense of aliveness is more intense than ever."

- Alan Jones on Death in the Desert Tradition

The early Christians known as the Desert Fathers and Mothers saw death as a companion who is always with us. They knew that living our life from the point of view of death was not a capitulation to despair but a wonderful way to clear the mind to approach every moment with delight.

- Robert Frager and James Fadiman on Death in Sufism

For Sufis, death is stepping across a threshold and being given another chance to reawaken. If we accept the premise that life and death are both gifts from the Divine, then the prospect of death becomes more a source of wonder than a cause for fear. The Sufi phrase "die before you die" can be interpreted to mean that death reveals what is truly important and what is not, and this is good information to have sooner rather than later.

- Rodney Smith on Death in Buddhism

Hospice worker Rodney Smith offers a Buddhist perspective on death. Death is occurring in each moment of life; nothing in the universe maintains itself even for an instant. To live our death means we do not maintain imaginary continuity. Everything is allowed to be just as it is, and death then merges into the moment itself. When we can meet death in this way, then it no longer exists as a reference point for our fear.

Spiritual Practices

Spiritual Practices

- Joseph Sharp on Using the "D" Words

Our words often hide stashes of denial and avoidance, says conscious dying advocate Joseph Sharp. It's important to acknowledge the fact of worldly impermanence. He suggests a simple practice: notice your use of euphemisms for "death" and "dying" and begin replacing them with the actual "d" words. He adds key questions to ask yourself in order to get the most out of this practice.

- Larry Rosenberg on Reminding Ourselves Constantly about Death

Rosenberg, a Buddhist practitioner, relates how a Buddhist teacher repeated the mantra "I'm going to die" before every talk, knowing this realization would keep him from any inflated ideas he might have of himself. Rosenberg suggests the practice of keeping mementos around to remind yourself of death. Why would you want to do that? The fear of death is a chronic form of anxiety that exhausts us. It's important to flush it out and to let in some fresh air.

- Stephen Levine on Finding a Perfect Day to Die

Stephen Levine in A Year to Live recalls a Native American saying, "Today is a good day to die for all the things of my life are present." A good day to die is when we are living our life instead of only thinking of it, when everything is up-to-date, and the heart is turned toward itself. He suggests a practice called "Taking a Day Off" that involves a daylong contemplation of seeing the world without ourselves in it.

- Philip Kapleau on The Day of the Dead

The Day of the Dead celebration in Mexico consists of a set of observances and rituals that create a symbolic mingling of life and death. Calaveras (living skeletons) rise up from their graves are seen merrily carrying on as they did during their earthly existence. Families welcome back the departed and have picnics in the cemetery. "Death is thus seen for what it is," writes Philip Kapleau, "a temporary point between what has been and what will be, and not as the black hole of oblivion." He relates this practice to its parallels in other cultures.

- Drew Leder on Imagining Death

One way of getting at your feelings about death, especially any fear you may be harboring or any expectations of pain and isolation, is to imagine death. Drew Leder offers a guided imagery meditation in which you imagine yourself as a leaf on a tree experiencing the natural passages of its life and death.

E-Courses

E-Courses

- Making Peace with Death and Dying

Led by Anne Boynton, Judith Helburn, and Pat Hoertdoerfer of Sage-ing International

Insights into the social, psychological, physical, and spiritual dimensions of facing our mortality.

- Sacred Presence with the Dying

Led by Megory Anderson of the Sacred Dying Foundation

Guidance on how to create a peaceful and sacred environment for a person who is dying.

- Learning to Accept Grief as a Lifelong Companion

Led by Joanne Turnbull and Claire Willis of Sage-ing International

An opportunity to explore obstacles to grieving, revise our narratives, and build resilience so we are better able to hold our sorrow.