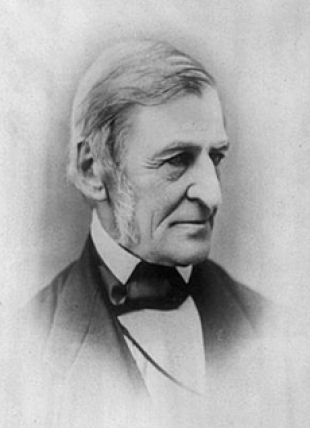

An extraordinary preacher, poet, essayist, and philosopher was born in this day in 1803. Ralph Waldo Emerson taught school and followed his father into the ministry. But six years later in 1832, after the death of his wife, he left the ministry. "God builds his temple in the heart on the ruins of churches and religions," he wrote. He settled down in Concord, Massachusetts, to pursue philosophy, which he defined as "reporting to his own mind the constitution of the universe." Emerson became an emissary of social change, and his work illustrated his wide range of interests.

This transcendentalist reveled in the chance to reach people as an independent lecturer and essayist in a time when people were looking for new spiritual directions. He offered a vision based on three interrelated principles: inwardness, unity, and right action. He developed a theory of spiritual life that affirmed the ability of every person to tap a transcendental inner power. He was ahead of his times with his mystical approach that blended an appreciation of nature, solitude, and ethical engagement.

Quotes

Quotes

To celebrate his birthday, take this quotation of his to heart:

"Life is a series of surprises. We do not guess today the mood, the pleasures of tomorrow, when we are building up our being."

Books

Books

- The Spiritual Teachings of Ralph Waldo Emerson by Richard Geldard

- The Spiritual Emerson: Essential Writings by David M. Robinson

Spiritual Practices

Spiritual Practices

Penning Friendship: In his beautiful essay “Friendship,” Emerson writes, “Our intellectual and active powers increase with our affection. The scholar sits down to write, and all his years of meditation do not furnish him with one good thought or happy expression; but it is necessary to write a letter to a friend, — and, forthwith, troops of gentle thoughts invest themselves, on every hand, with chosen words.”

Today, write a letter to a friend who brings out your deepest affections and best thoughts. Consider writing as Emerson would have, with pen and paper, and hand-delivering it to your unsuspecting loved one.

Snatching the Ideal from the Jaws of Routine: In his famous Phi Beta Kappa address in 1837, now known as “The American Scholar,” Emerson sounds a note of caution that still resounds with urgency. He worried about the increasing monetization, specialization, and routinization of work; specifically, he worried that humankind was being “metamorphosed into a thing, into many things. The planter, who is Man sent out into the field to gather food, is seldom cheered by any idea of the true dignity of his ministry. He sees his bushel and his cart, and nothing beyond, and sinks into the farmer, instead of Man on the farm. The tradesman scarcely ever gives an ideal worth to his work, but is ridden by the routine of his craft, and the soul is subject to dollars. The priest becomes a form; the attorney a statute-book; the mechanic a machine; the sailor a rope of the ship.”

Either in silent meditation or — better — in intentional conversation with someone who knows you well, reflect on the tasks of your day and the purpose of your work. Dig deep and reach high to recover the “ideal worth” of each task and the “ministry” of your profession.