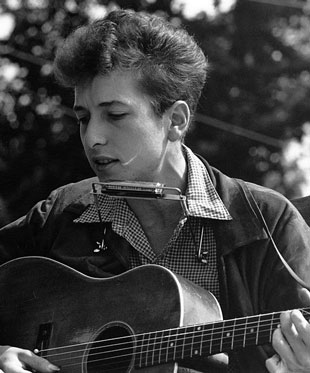

Robert Allen Zimmerman was born in Hibbing, Minnesota in 1941, and christened himself Bob Dylan sometime before 1961 when he was discovered playing small clubs in Greenwich Village. Influenced by his musical hero Woody Guthrie and others, he is both the inheritor and the innovator of the tradition of American folk music.

Dylan’s maturing as an artist synchronized with the Civil Rights movement and the demand for topical folk songs to reflect the headlines. In the early '60s, he thrived on writing songs for protests and marches that expressed both anger and hopefulness. His songs inspired activism by alluding to historic injustices — as in “The Ballad of Emmett Till” — and by drawing attention to the urgency of the present — as in “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall,” about the threat of nuclear war.

Dylan wrote more universal anthems as well: “The Times They Are a-Changing” and “Blowing in the Wind” express an intolerance towards the status quo, but without the specific references of the journalistic songs. Their ambiguity makes them an invaluable resource, adaptable to any movement for progress.

The quintessentially American thing about Dylan is his ability to continually reinvent himself. He continued to write political songs over the years, but he set out to craft a career for himself as carefully as he crafted lyrics, adding more personal songs to his repertoire and exploring other genres and sounds. This shift lent an even more remarkable range to an oeuvre already marked by anger, hope, and humor. From 1964’s cathartic “It Ain’t Me Babe,” which aims protest’s rage against love itself, to 1997’s sweet-toned “To Make You Feel My Love,” a traditional love song well-suited for weddings, one thing is undeniable: Dylan is a consummate songwriter who both eludes and exceeds our expectations. The Swedish Academy recognized this, and in 2016, Dylan became the first songwriter ever to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

To Name This Day:

Quotes

Quotes

“If you can't speak out against this kind of thing, a crime that's so unjust,

Your eyes are filled with dead men's dirt, your mind is filled with dust.

Your arms and legs they must be in shackles and chains, and your blood it must refuse to flow,

For you let this human race fall down so God-awful low!

This song is just a reminder to remind your fellow man

That this kind of thing still lives today in that ghost-robed Ku Klux Klan.

But if all of us folks that thinks alike, if we gave all we could give,

We could make this great land of ours a greater place to live.”

— from “The Death of Emmett Till”

“How many years can a mountain exist

Before it is washed to the sea?

How many years can some people exist

Before they're allowed to be free?

How many times can a man turn his head

And pretend that he just doesn't see?

The answer, my friend, is blowin' in the wind

The answer is blowin' in the wind.”

— from “Blowin’ in the Wind”

“In a soldier's stance, I aimed my hand at the mongrel dogs who teach

Fearing not that I'd become my enemy in the instant that I preach

My existence led by confusion boats, mutiny from stern to bow

Ah, but I was so much older then, I'm younger than that now

Yes, my guard stood hard when abstract threats too noble to neglect

Deceived me into thinking I had something to protect

Good and bad, I define these terms quite clear, no doubt, somehow

Ah, but I was so much older then I'm younger than that now.”

— from “My Back Pages"

“In the most unlikely setting of all — the commercial gramophone record — [Dylan] gave back to the language of poetry its elevated style, lost since the Romantics. Not to sing of eternities, but to speak of what was happening around us. As if the oracle of Delphi were reading the evening news.”

— Professor Horace Engdahl, presenting Dyan with the Nobel Prize in Literature

Practices

Practices

Reactivate an Anthem: In 2018, “The Times They Are a-Changing” was performed at the March for Our Lives rally against gun violence. Listen as Dylan sings the song in this video and note lines that seem to be about the time we are living in now. Write them down if you like, and reflect on what they might refer to now. How might you translate their poetic power into action in your own community?