The takeaway from How I Became a Tree might simply be: We would all do well by ourselves and for the world if we lived more like plants.

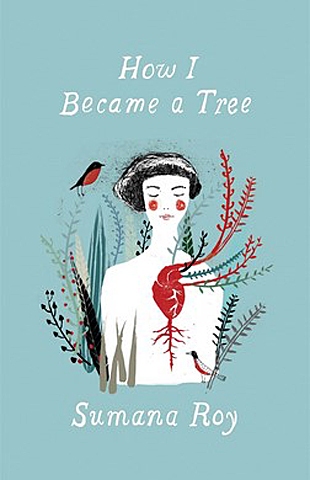

First published in India in 2017, this beautiful book is now published in North America by one of our finest university presses. The author, Sumana Roy, is a professor of English and creative writing at Ashoka University in Haryana, in the north of India.

She admires trees in language that is reminiscent of the writings of Henry David Thoreau. Explaining how this study of hers got started, she writes: “I liked … how trees thrived on things that were still freely available — water, air and sunlight; and no mortgage in spite of their lifelong occupation of land.” Her praise also includes: “It was impossible to rush plants, to tell a tree to 'hurry up.' ” And, “their world remained unaffected by changes in governments…. And so my attraction to the tree and its complete indifference to the hypnosis of news.”

You can see why she might prefer to be a tree. These are such appealing, healing qualities that feel alien to most human experience.

Growing older, too, seems to Sumana Roy to be something valued in tree life, in contrast to human life. In fact, “tree time,” as she refers to the way in which trees approach things, is summarized: “seize the moment, living in the present … a life without worries for the future or regret for the past. There’s sunlight: gulp, swallow, eat; there’s night: rest.”

She then dismantles old notions from fables and literature about trees, for example, the portrayal of men as trees and women as flowers. This leads her to praise more aspects of tree life: “I liked what I thought was the restraint in plants. It wasn’t actually restraint but a natural order that we like to call balance. There was no gluttony, no anorexia — plants ate only as much as they needed.”

She writes in the past tense, as if relaying her thoughts and investigations and discovery of meaning to us as they came to her. The book is full of “I soon realized…” and “This led me to discover…”

Many of her observations are ones that only someone who can give birth might make: “This beauty of bareness I began to see later as the beauty of barrenness, say, the beauty of a desert, for in being shorn of flowers and leaves, these trees had managed to escape the burden and technology of reproduction.”

Two of our favorite chapters were devoted to Rabindranath Tagore’s affection for trees and dedication to cultivating them. She speaks of his “baptizing” trees with names and loving them as only a lover might do.

There are also fascinating chapters on seeing plants as children and on a revaluing and reimagining of human sex, romance, and love in light of trees and their ways of being. All of these insights may appear, at first, as simply philosophical or even fantasy, but this is a book for looking deeper. (See the excerpt accompanying this review.)