Christophe Honoré’s Sorry Angel shows how deeply spiritual a film can be, even as its message is wrapped in relentless melancholy. Set mostly in early 1990s Paris, the film’s main characters, 35-year-old Jacques (Pierre Deladonchamps) and 22-year-old Arthur (Vincent Lacoste), are each on separate journeys, one feeling the weight of looming death all around him, the other enjoying the fruits of youthful sexual freedom. Their chance meeting in a movie theater brings those journeys together for a brief period, one in which the gravity of Jacques’ sadness and the levity of Arthur’s gumption combine to create a combustible chemistry that pushes both of them into connections for which they both at first seem too cool, too caustic, and too self-obsessed.

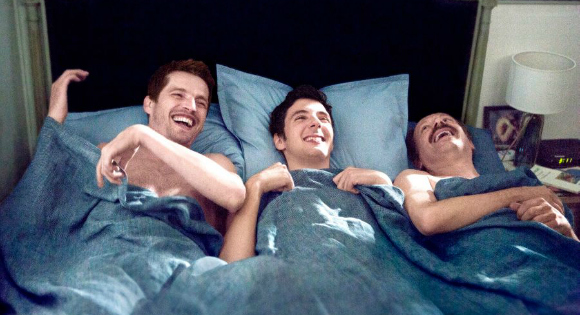

Jacques has seen much in his 35 years. He is raising a young son whose custody he shares with a female friend, and he is trying to break free from the clutches of a past lover, Marco (Thomas Gonzalez), who is in the late stages of a battle with AIDS. Jacques himself is in a healthier, but still precarious, battle with the virus himself, and the shadow of the epidemic permeates every aspect of his life, even as he enjoys fame as a novelist and a beautifully intimate but chaste relationship with his friend and neighbor Mathieu (Denis Podalydès). He wavers between being charming and testy, warm and frigid, and he has settled into a groove of casual encounters that keep him from having to give too much or change at all.

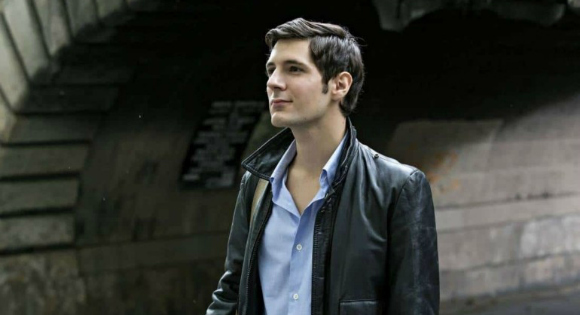

Arthur has seen nearly nothing. A Breton student with an uncommonly cocky flair, he is sowing oats where he can, flirting with friends of all sexes and genders, relying on the sparkle of his cherubic smile and lithe frame. When he tells a female friend that he’s not going to spend the night with her because she owns no novels, the trappings of his presumptuous personality are laid bare. He knows he deserves the best, because he believes he is the best. This immature — yet infectious — hubris directly contrasts with Jacques’ somber demeanor, but in the scenes leading up to their first encounter, they are shown to share at least one quality: They both have an empty space to fill, and neither quite knows how to fill it.

As this love story unfolds, its most surprising feature is how agilely it avoids easy sentimentality. The quips are sharp and acerbic, the dismissals and disses ample, as the director refuses to suggest that any of his characters either hope to be saints or fear they are sinners. The sex is open and guilt-free, the relationships fluid and happily ambiguous. And with mawkishness nowhere to be found, the film avoids using illness as a depressing plot driver, instead responding to its grim realities with a celebration of connections in the face of impending collapse. It’s an unapologetically queer and honest story, fixated on the loss of innocence and the loss of lives in the gay community, and while it never shies away from exploring mortality, the film ends up saying more about the risk of truly living than it does about the scariness of death.

The film’s title perfectly encapsulates the see-sawing between sass and sincerity that is fully embodied by Honoré’s tone and his characters. From scene to scene, the English title, Sorry Angel, and the French title, which basically translates to “Please love and run fast,” take on a variety of meanings, constantly moving from plea to promise to demand to apology and back again, while always remaining slyly cheeky.

This is a historical tale, about a terrifying time when it was particularly dangerous to love and alarmingly easy to lose, but it’s also a perennial and piquant story, underlining the fact that love and loss are always in the mix, no matter how invincible and untouchable humans might often think they are. It’s a wistful remembrance and a galvanizing reminder, a mournful memorial and a sharp nudge, like the memory of a long-lost friend’s biting wit that urges you to go on, even though they could not.