Mani Haghighi’s Pig is definitely not for everyone. And it really doesn’t seem like Haghighi minds this fact. Instead of attempting to keep this brilliantly bonkers satire tastefully balanced, Haghighi tips the scales toward excess, crafting a deliriously unserious investigation of very serious themes. For those who are willing to follow his characters into the depths beneath the gonzo surface, Haghighi has much to say about the artist’s ego, the censorship of creative voices, and the dangers of making art from the heart in an age of immediate social media takedowns and devastatingly short attention spans.

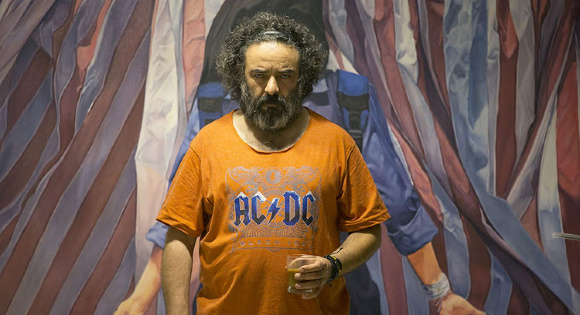

The film’s grumpy hero is blacklisted Iranian film director Hasan Kasmai, played with a paunchy pout by the hilarious Hasan Majuni. Hasan is a bit of a manchild, surrounded and supported through his government-sanctioned artistic alienation by smart, capable women, including his wife Goli (Leili Rashidi), his daughter Alma (Ainaz Azarhoush), his leading lady Shiva (Leila Hatami), and his mother Jeyran (Mina Jafarzadeh). But even with this support, Hasan is losing his mind, doomed to direct a tacky bug spray television commercial while he waits for the go-ahead to again make the films he wants to make. In the meantime, he fumes with jealousy over the success of stylish hack Sohrab Saidi (Ali Mosaffa) and sulks in the comfort of a rumpled AC/DC t-shirt.

Hasan is already feeling left out of every party, so when a serial killer begins to pick off famous Iranian film directors one by one, decapitating them and leaving their foreheads emblazoned with the carved word “Khook” (“Pig” in Farsi) carved into their foreheads, Hasan’s response is as self-centered as one would expect from an out-of-work egotist: He wonders why the serial killer isn’t stalking him as well. He is dying for attention, even if that might mean actually dying. And as the body count rises, Hasan becomes increasingly embroiled in both the hunt for the murderer and in his own ridiculous desire to be re-legitimized by being hunted himself.

It might be enough for Haghighi to set out to make a simply silly satire, one that skewers the fragile egos of overgrown and overeager artists (and in an inspired turn, the film’s murdered filmmakers are real Iranian filmmakers, including Haghighi himself), but Haghighi has much more to question and say than merely showcasing the private pain of stunted creativity. Supplementing the broadly entertaining story of Hasan’s journey to confront the “Khook” killer and regain his stature as an admired auteur, is a more subtle interrogation. Haghighi is asking questions of a government eager to pressure artists to censor their own voices and of a society strangely walking a line between a strangely stilted brand of conservatism and a brazenly modern hunger for sensationalism.

The fact that Haghighi is able to thread these more nuanced themes in between the very funny dialogue and situations of Hasan’s story is a true feat, and it’s a wonder to behold how intricately he weaves critique and comedy together, especially since a false move of his own could ostensibly get him censored himself at any time. But Haghighi doesn’t miss a beat. The hilarity is always undergirded by heart and humanity. The satire is always supplemented by serious inquiry.

The darkly delightful twists and turns of Pig are many, including surprising deaths, reveals, and connections, but the moving messages of an artist’s attempt to adjust his ego amidst literal creative death and a society’s existential crisis of fascination and boredom are the film’s lasting gifts. There’s a spiritual question at the root of all of these bloody shenanigans: Is art worth the danger and does anybody actually care in the end? It’s a question that could be asked of both ancient cave paintings and of the latest film coming out of a censorship-fraught country.

Hasan gets some answers at the film’s tense and violent end, but Haghighi seems more interested in his audience taking the questions with them, and continuing to apply them to the next piece of art or the next wounded artist’s ego they encounter. His characters fight for freedom in a fawning but fickle world that is watching, but might be distracted at any moment by something more exciting. Directly confronting this short attention span conundrum, Haghighi’s film entertains and enlightens in equal measure, while opening international audience eyes to a society both foreign and familiar, to characters both particular and perennial, and to arguments that seem both newly urgent and stitched into the fraught fabric of millennia.

Pig has been showing at film festivals. Watch for it in your local art house theater (or request it be booked) and for a DVD release.