"For Thurman, the surest alternative and antidote to the climate of fear was the cause of radical nonviolence. It was the insistence, against all around him, that a life lived without fear was still possible. Radical nonviolence is the subject of the final chapter of Jesus and the Disinherited, a chapter Thurman titled 'Love.' Seeing radical nonviolence as a form of love has obvious Christian, as well as Hindu, roots, and much of great beauty has been written on this theme. However, thinking of radical nonviolence as a form of love often leads people into misconceptions. It is a form of love that can be as penetrating and painful as a dentist’s drill, but a drill that can hurt the dentist as much as the patient. Let me suggest another way to think about Thurman’s understanding: nonviolence is a discipline of structured fearlessness. This is certainly how Black Americans saw Gandhi. Benjamin Mays, who visited with Gandhi a year after Thurman, wrote in 1937 that 'the cardinal principles of nonviolence are love and fearlessness,' and claimed that Gandhi 'did more than any other man to dispel fear from the Indian mind and make Indians proud to be Indians … [for] when an oppressed race ceases to be afraid, it is free.' "

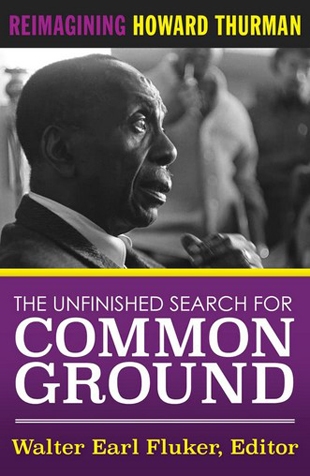

The Unfinished Search for Common Ground Reimagining Howard Thurman

Nonviolence: a discipline of structured fearlessness.