A blank screen fills with Spanish words: "Esta historia es una réplica del original." ("This story is a replica of the original.") Thus begins Alonso Ruizpalacios’ imaginative riff on a real-life mystery, the Christmas Eve 1985 theft of 140 Mayan and Aztec artifacts from Mexico City’s National Museum of Anthropology. From this factual seed, Ruizpalacios spreads tendrils of fictionalized fantasy, crafting a wondrous film that often feels like both a delicate character study in the shape of a buddy action-comedy and an astute interrogation of cultural theft in the shape of a zany heist film. Like its delightful, searching, complicated characters, Museo is a puzzlebox. It's a crowd-pleasing fable of foolishness on its surface, with much wiser things to say hidden amongst its many underlying layers.

In Ruizpalacios’ invented scenario, our antiheroes are Juan (Gael García Bernal) and Wilson (Leonardo Ortizgris), two childhood friends wiling away their adult days in the drowsy Mexico City suburb of Satélite, stretching their delayed veterinarian school studies way past their expiration dates. Juan is the mouthier mastermind (though he is regularly belittled by his relatives, who insist on calling him "Shorty," constantly needling at his physical and character flaws). Wilson is Juan’s loyal, amiable sidekick and is also devoted to caring for his ailing father, a connection Juan can’t quite secure with his own distant dad (Alfredo Castro).

The early endearing exchanges between these curious man-children ground the more outlandish later whims of the film in effortless authenticity. Long before these two lovable losers set off on their ill-conceived museum break, the gentle humor in each actor’s performance lays the necessary foundation to keep the audience rooting for the bumblers, even as their decisions grow more and more reckless.

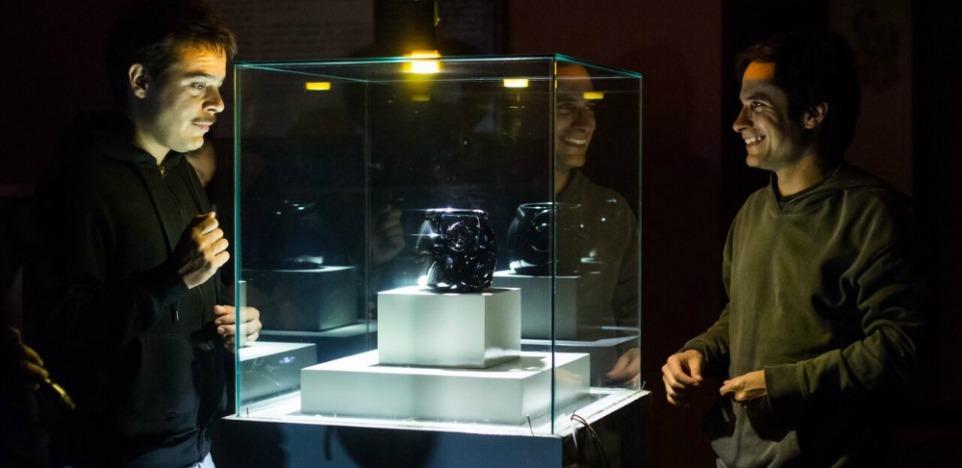

And increasingly reckless the decisions do grow. Desperate for some adventure, Juan convinces Wilson to use the holiday lull to go spelunking in the National Museum of Anthropology’s beloved collection of indigenous artifacts. Having succeeded, they then naively set out to sell their bounty on a market too dangerous and intricate for their guileless shenanigans. At every turn, their wide-eyed innocence gives the reality of their guilt, the fact that they have just pulled off the biggest museum heist in history, an odd and awkward grace.

Throughout, the seriousness of the crime is weighed against Juan’s search for a purpose and Wilson’s overgenerous desire to help him find one. Satélite has nothing for Juan, whose ambition outruns his practical skills. Though Wilson’s ambitions are more modest, his love for his friend proves such an integral part of his own identity that these also-rans are two halves of a whole: Juan’s foolhardy drive in constant need of Wilson’s passive support, and vice versa. Ruizpalacios never affirms their crime, but he adds effective and evocative shades that flesh out the human beings behind the sensational news story. Juan and Wilson are both in search of themselves, identities they want to own, identities that elude them at every turn.

This compelling study in earnest enabling would make Museo a good film — but what catapults it from being simply good to being truly great is that it takes its nuanced focus on identity and ownership and expands it from the individual to the cultural. The question of cultural theft begins to seep into the plot once Juan and Wilson have made their getaway and are seeking a place to drop their treasures for hard cash. An encounter with a white English collector of indigenous art begins to gnaw at Juan, and what was intended as a quick exchange becomes a profound and disturbing argument. At the core of the fight is a potent question: Who actually owns art when it’s been stolen from a colonized culture? And if that art is stolen in return, is it a crime or is it justice? Can an individual act that seems selfish on the surface be redeemed by digging deeper for the good intentions?

Museo does not offer clean answers to any of its questions, but the film’s point of view (complete with hindsight-laden narration by a wiser Wilson) suggests that the reasons people do the things they do will often remain a mystery, not only to the outside observer, but also to the doer. That Ruizpalacios creates a world in which it seems plausible to wholly identify with these clumsy criminals is a dynamic feat that will haunt long after the achingly melancholic final scene in which a character asks, "Why ruin a good story with the truth?" By Museo’s finale, the truth of this replica of the original facts seems far deeper and troubling than any cut-and-dry report you might catch on the nightly news.