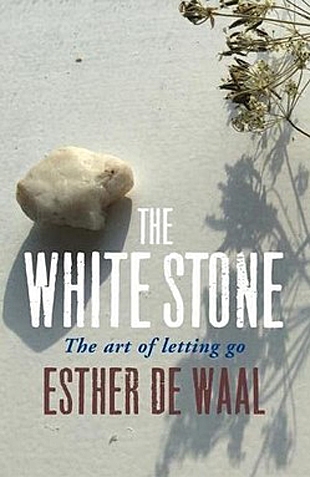

The white stone of the title is not figurative or metaphorical; it is a literal rock that the author carries in her pocket, for the “reassurance of its presence.” Esther de Waal is one of our Living Spiritual Teachers. In this new book, the popular author of Christian classics on Benedictine and Celtic themes looks deeply at the big and small ways we all must learn to “let go” of what we know in order to change and grow through life.

The focus of her own letting go, now late in life (she was born in 1930), was a recent move within England from her family home near the Welsh border, with natural beauty and landscape, into the urban environment of Oxford.

The cottage she left behind, her longtime home, “nestles into the side of a gently sloping hill … built of the local Herefordshire red sandstone as are all the nearby farms and barns” in a part of Britain known as the Welsh Marches. It was a place that defined and nurtured her. These things she exchanged for “crowded pavement in a busy city.”

“This is where I belong,” de Waal writes about her old house. And yet this thin book is a contemplation spurred by her leaving it, doing so for the good of what may happen next.

There are many applications for de Waal’s spiritual wisdom on this theme that relate to death and dying, grief and grieving, and welcoming and embracing. One chapter focuses on the Book of Psalms, in which, as de Waal explains, “newness is a constant theme” and “a cause of rejoicing: in a process of continual transformation.”

Another chapter focuses on the monastic tradition — specifically the spiritual practices of stability, listening, and obedience. Then there are additional meditations on themes such as mercy, forgiveness, and death. But before death, de Waal focuses on what she calls “diminishment.” In this essay-like-chapter she quotes artists ranging from Thomas Merton to Ansel Adams to Marie Louise Motesiczky and concludes:

“I associate with the ancient oak beside the cottage gate — stability, rootedness, strength. It is a safeguard against the self-pity that can all too easily become so attractive and so insidious. I want to prepare for the years ahead that almost inevitably will bring some form of suffering. There will be the physical diminishments, the loss of memory, or of sight or hearing, the restrictions that a frail body will impose. There will be damage to the fabric of myself that cannot be repaired. And above all there will be times when I feel huge sadness, washing over me like a great wave, when I realize that my life will disappear and I shall not be there to see how my family are living, how my children and my grandchildren are growing, and how they will be in a world that I cannot begin to imagine. This will be the final letting go.”

The White Stone is full of spiritual practices, some quite specific and immediately helpful, not only for letting go, but for embracing what is new. See the excerpt accompanying this review for an example of these.