How would you describe your relationship with your body? Do you feel you understand your body in relationship to others? And how is the “body politic” — our democratic institutions and often dysfunctional communities — affected by our inability to understand what bodies mean and do?

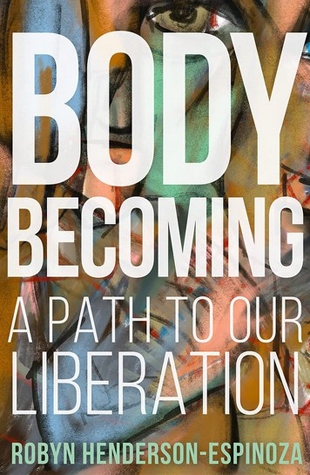

Robyn Henderson-Espinoza, a transqueer activist, Latinx scholar, and public theologian has lived, taught, and reflected on these issues. The book begins with some personal story: “I have been on a five-year journey developing a relationship with my body and further deepening my relationship with what is sensate and seeking understanding in what it means to participate in my own becoming (em)bodied. Obviously, I’ve been on a much longer journey with my body, but these last five years, I’ve intentionally committed to befriending my body — my NonBinary Transgender Latinx body. As my therapist has asked me, 'How can you be your own best friend?' ”

Such a journey of NonBinary Transgender discovery is of a body becoming. But Henderson-Espinoza explains that every body is (or should be) understood as becoming. Their explanations of these processes can be at times philosophical, but simultaneously, if you read carefully, they are inspirational. For instance: “And becoming is central to the work of becoming bodied because the more comfortable we are with our own felt sense of the body, the greater the work will be when we intentionally move externally in relation to other bodies and participate in a collective becoming.”

Every person — every body — experiences pain and healing. And every person — every body — needs to understand itself and its ways of becoming in order for communities, nations, and others forms of the body politic to function in healthy ways. We all have a lot to learn. As the author explains: “We have been taught not to be in relationship with ourselves, and that orientation further accelerates an attitude and practice of not being in relationship with one another.”

Henderson-Espinoza graduated from Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary and earned a PhD at The University of Denver/Iliff School of Theology, studying philosophy, theology, ethics, and culture. Readers with interests in academic discussions of these disciplines will perhaps most of all enjoy this book. For example, Henderson-Espinoza holds up panentheism (see Jay McDaniels' blog post on this topic) and points to animism, revealing a willingness to move beyond traditional theological categories. They write, “In the language of theology and panentheism, we might say that God — in motion and relationship — is in all things and willing all things to come to life. In the language and lens of animism, it is the cognization and awareness that all things are endowed with spirit and life, something that Christian theology erased and never incorporated into the life of the church.”

But the book is also written with a popular touch, including the sort of memoir quoted above, and practical applications for any spirituality-sensitive person who wants to feel more at home in their body. These include questions you may ask yourself to become more fully embodied and Henderson-Espinoza’s own helpful reflections of feeling grounded: “I feel a deep relaxation in my body-soul. I am knit together, like I am intended to be. I am being held with sacred awareness for my healing.”

Body Becoming includes thinking about embodiment, imagining how greater embodiment might lead to healing of our body politic, and physical practices that each person might do with this new wisdom.

Henderson-Espinoza is frequently willing to share vulnerabilities and self-discovery with the reader. For example, they also reveal that they are on the autism spectrum. This was a blessing, they explain: “Autism is what makes me me in so many ways, and it’s what has given me the freedom to think more critically and creatively about my body, my being, my motion in the world.”