Like many, we were influenced by reading Thoreau at an early age: the classic Walden, of course, but also other books including Cape Cod, The Maine Woods, the essay “Walking,” and the volumes of his beautiful Journal — all published for the first time more than 150 years ago. Author Ben Shattuck revisits these works, but more importantly, follows literally in Thoreau’s footsteps to the places Thoreau was writing about all those years ago. In the process, Shattuck makes important discoveries about his own life and purpose.

Six Walks is a kind of spiritual travelogue, a therapeutic book without the therapy, for anyone willing to pause long enough to notice where the green of the hills differentiates from the green of the fields, and how snow often looks like waves upon a sea.

This is a book for learning the spiritual practices of attention and wonder from a master teacher — both Thoreau, and his student, Shattuck.

Inspired by reading Thoreau’s Cape Cod, one day Shattuck (a trained writer who also operates a New England general store on the coast of Massachusetts) suddenly knew he had to leave home and retrace the walking route Thoreau took and wrote about so helpfully. “I would walk the outer beaches, from the elbow [of the Cape] to Provincetown’s fingertip, as Henry had done. If it took a day, or three, I didn’t mind…. Before I walked out the door that morning, I also put a notebook in my backpack, not because I ever journaled or made sketches, but because Henry had, and I wanted to try someone else’s habits for a few days.”

This is the approach of someone willing to be a novice, a beginner — an essential posture for anyone seeking to grow in wisdom and understanding. The reader senses Shattuck’s self-knowledge growing like tendrils from this point, early on in the book, through its final chapter.

He does not feel obliged to follow Thoreau’s path in every detail. For example, before walking to Wachusett Mountain, Shattuck tells us: “Henry walked with a friend from his home in Concord, Massachusetts, all the way to the summit, which I didn’t do, because I didn’t want to trudge through suburbia.” Shattuck takes a much longer way around.

Over and over, he meets people on his way, and describes settings in ways that make you feel you are also there. And he repeats conversations with ordinary people, such as when he meets Paul:

“This place,” Paul said, pointing to the ground, to the mountain we shared then, “I come here every day. I’m addicted to it. Sometimes I say to myself, 'I don’t have time for this,' but I always come.”

Shattuck has the broadest possible understanding of what is divine and what is divinity. His walking trips take place over many years, in both the daytime and at night, and often in the company of others. This maxim of Thoreau on the value of walking permeates every page: “There is … this consolation to the most way-worn traveler, upon the dustiest road, that the path his feet describe is so perfectly symbolical of human life.”

Wonder and awe permeate Thoreau’s books and are gleaned well by Shattuck through the kinesthetic of a long, tiring, attentive walk. He closes with another quote from Thoreau’s Journal, implying that he (Shattuck) came to understand this in an embodied way: “There, in that Well Meadow Field, perhaps, I feel in my element again, as when a fish is put back into the water…. All things go smoothly as the axle of the universe.”

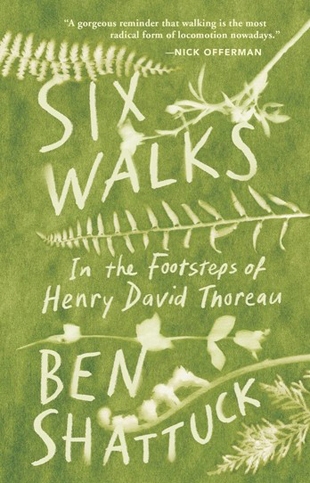

Occasional black-and-white drawings effectively convey the feel of some of the flora and fauna along the way; and the notes section at the back of the book provide sources for every Thoreau quotation.