Sitting in a car on a bluff overlooking the Pacific ocean, Frank Rogers’ recently-institutionalized sister Linda turned to him for help. “You were like this once,” she said. “What did you do to get better?” Rogers gave what answer he could. Weeks later, his sister took her life.

Cradled in the Arms of Compassion is the answer he wished he could have given her. It tells the story of a beloved professor of spiritual practices whose unmetabolized trauma almost undid him. As Rogers struggles not to come undone, he discovers the movements of what he will later formulate as the Compassion Practice (see Practicing Compassion); his “quest merely to stay alive was alchemized into a life’s work.”

So that others might live, feel validated, and not hide in shame, Rogers has written with clarity and openness about his own childhood sexual abuse and the trauma it left in his body. As a result of this sometimes painful vulnerability, there were times when I wanted to put the book down and not pick it up again.

But after meeting little Frank, a Catholic schoolboy in San Mateo, California, I could not abandon him. I had to keep picking him up. I had to keep reading until what happened to him on page 6 and page 109 and page 207 was fully validated. I wanted to accompany him through the caverns of trauma and hold him in the light of healing.

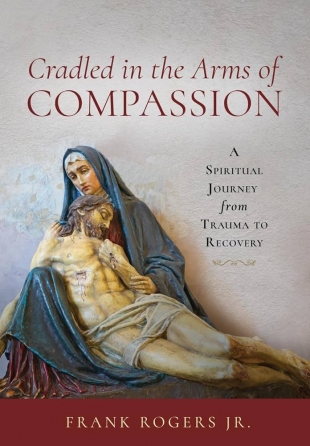

Indeed, the pieta, an image of Mary holding crucified Jesus, is central to the meditations Rogers uses in order to heal. The pieta comes to represent the relationship between a wounded beloved and a source of ultimate compassion. To enter the hellish caverns that house traumatic memory, Rogers had to discover a sacred source – for him, Shekina (the female presence of God)– that held him in cosmic, unconditional, steadying compassion.

Similarly, Rogers had to learn to tenderly hold his own feelings. In order to follow the promptings of body and memory to journey through what felt like the “depths of hell,” he had to accept that every interior movement comes to us as an ally. What a momentous shift in perspective for someone triggered by horrific images day and night, someone who had made plans to take his own life!

“To be sure,” he writes, “in their cry to get our attention, [these interior movements] usually overwhelm us with their force, prompting us to try to suppress, numb, or manage these interior psychic states.”

However, “emotions, impulses, and interior movements of all kinds are present for a reason. They are the cries of unmet needs or unhealed wounds aching to be heard. When we listen to them with curiosity and tend to them with compassion, they not only relax and realign, they allow us to access our best selves where our greatest spiritual resources are found.”

Rogers taught himself, and teaches us, to cradle our interior movements, no matter how loud or crass or threatening — to hold them tenderly, befriend them, take their hands, and say, “I am ready to go where you are trying to lead me.”

Like all good memoir, Cradled in the Arms of Compassion has a robust narrative engine – the reader is led along, page-by-page, with questions, curiosities, and a desire to see what “happens next.” And it also has gratifying character development that leads to readerly investment in Rogers, his sister Linda, and even his mother.

But the memoir offers much more as well because the practices that heal him – from imaginative meditations to creative arts — are a rich part of the narrative itself. Much of the memoir is given over to descriptions of the before, during, and after of the meditative experiences that transform his trauma: we watch as he befriends a “negative” emotion; we see the caverns he navigates as he looks for the scared boy inside, and then we experience, with him, the release of tension and the warmth of reunion.

As we readers accompany Rogers, we can substitute our own trauma for his and follow along, befriending whatever moves inside us, imagining the landscape where our scared and abandoned selves are lodged, holding those parts, and maybe metabolizing a bit of our own pain. While healing from any kind of trauma can be circular and repetitive, the hope infused in this practice-filled memoir makes good on his sister’s question, “How did you get better?”

The answer, this book, is not just a gift to Linda but to us as well. May we all claim getting better.