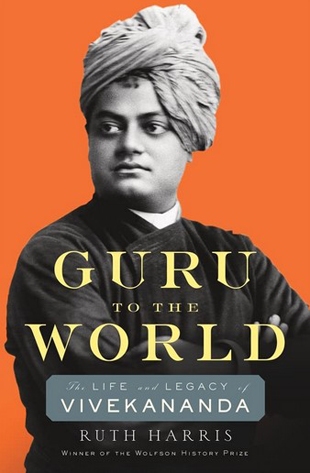

We know him as the one who brought Hinduism to the West, starting at the Parliament of World Religions in Chicago in 1893. “Sisters and brothers of America,” he famously began his opening speech. A monk, philosopher, author, and teacher, he was also inheritor of the mantle of Sri Ramakrishna. He died much too young — just 39 years old.

This will be the standard biography of him for years to come. Author Ruth Harris, a University of Oxford research fellow, has done an admirable job, approaching the project not as a devotee but a scholar, with critical acumen yet fairness in matters of religious belief and practice. It is a book for serious students of religion, with 420 pages of text, focusing not just on the spirituality of the great teacher, but on “the tensions in his emotional world and the sometimes contradictory spiritual message that he constantly recalibrated for different individuals and publics.” It contains 80 densely-packed pages of end notes.

Regarding that “recalibration,” Harris looks, for instance, at how Vivekananda relied on the orientalist cliché of “Eastern wisdom” before Western crowds, implying implicit goodness of India and Indian religion, as against the West’s materialism; but then back home he was often an astute critic of stereotypes and narrow, old-fashioned ways.

It was common for people in the West to perceive in Vivekananda a natural dignity, and he used this to his advantage, educating thousands in the ways of renunciation, meditation, and soulfulness.

At times, he upset members of his own religious order by his focus on pairing Karma yoga (yoga of action, rather than knowledge, meditation, or devotion) with Advaita Vedanta. This was how he separated from Ramakrishna, “who feared that worldliness might lurk behind a veil of altruism, contaminating such philanthropy with self-interest,” in Harris’s analysis. But it was also one reason for the strong appeal of Vivekananda’s teaching in western cities.

For an example of Vivekananda’s attempt to apply Eastern wisdom to Western values — blending spiritual practices of Justice and Devotion — see the excerpt accompanying this review.

Vivekananda spoke to crowds and his students about the virtues of rational inquiry, and yet he also recognized a human being’s inner divinity — something he learned from Ramakrishna — which naturally leads to playfulness, joy, and ecstasy. Somehow, Vivekananda blended these qualities in his life and teaching, and this is one of many powerful messages in this important biography.