W.A. Mathieu, a composer, writes in Bridge of Waves: "You sing a song and it is a perfectly good song. I sing a different song, also a perfectly good one. Polyphony is what happens when we sing our songs together and the relationship between them is more rich and pleasing than either song by itself."

Think of Nymphomaniac as a polyphonic piece where Lars von Trier tells the story of the adventures and misfortunes of a female sex addict while also singing a song filled with fascinating and arcane references to art, history, religion, music, and literature.

These connections beg for our attention and participation. If groups of strangers have been gathering at cafes all over the world to talk about death and all its complexities, why not do the same thing for sex and sexual addiction? Here are some preliminary notes to get you started.

The National Council on Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity has defined sexual addiction as "engaging in persistent and escalating patterns of sexual behavior acted out despite increasing negative consequences to self and others."

In an article on "What Is Sexual Addiction", it is described as "a progressive intimacy disorder characterized by compulsive sexual thoughts and actions. Many sex addicts do not seek physical gratification but are attracted to an excessive need for power, dominance, control, revenge, or a perverted expression of anger."

More and more women and men are taking part in phone sex, the use of escort services, and computer pornography. An increasing number of those who have become addicted and can't stop the compulsive behavior are looking for help from high-priced rehab centers. The distorted lens of our culture presents sex as love, power, freedom, pleasure, and the ultimate game.

In 1964, Albert Ellis wrote Nymphomania: A Study of the Oversexed Woman and in 1975 Robert Stoller put forward the companion term Don Juanism to describe sexual addiction in men.

It isn't that big a surprise that the Danish writer and director Lars von Trier has taken up the challenge of providing a complex, lengthy, and controversial portrait of a female sex addict and her experiences from childhood to adulthood. His prior films include Breaking the Waves (a glorious paean to the mighty power of love with a stunning performance by Emily Watson), Dogville (an innovatively staged and brilliantly acted parable about a fear-based community in the 1930s whose greed, hatred, small-mindedness, and entitlement come to the fore in their reactions to a stranger), and Melancholia (a mind-blowing end-of-the world drama that challenges us to take stock of our beliefs, feelings, and fears about death). Now he has fashioned a four-hour drama that takes us on philosophical and spiritual ride where female sexuality turns out to be a tuning fork for many astonishing aspects of the human adventure.

1. A Long and Moral Story

"It will be long and moral, I'm afraid," says Joe of the story of her life and sexual adventures.

In the opening scene of the film, Seligman (Stellan Skarsgard), a middle-aged bachelor, turns out to be a modern day Good Samaritan. After finding a bruised and beaten woman in an alley, he takes her back to his apartment. He honors her request not to be taken to the hospital and treats her wounds.

At his request, Joe (Charlotte Gainsbourg) begins to tell him the story of her life. She admits having a great interest in her genitals at age 2. That fascination took hold of her and by the time she was 5, she and a friend had found a way of masturbating while sliding across the wet bathroom floor. In a flashback, we see Joe (Stacy Martin) at the age of 15 asking Jerome (Shia LaBeouf), a boy with a fondness for motorcycles, to take her virginity. He does so in a perfunctory manner and she is not flooded with emotions. But the sexual act nonetheless becomes for her an obsession.

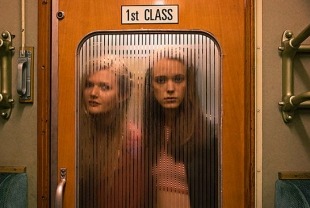

Goaded on by a promiscuous friend B (Sophie Kennedy Clark), Joe competes to see which of them can gather more sexual conquests on a train. They both score with more men than they expected but it all comes down to whether or not Joe can convince a straight-arrow married man to do the deed.

As Seligman listens to Joe's tale about the girls seducing men on the train, he relates it to his knowledge of the art of fly-fishing. Both of them are startled by the connections he makes. Intrigued by her story and delighting in the chance to chime in with his commentary Seligman feels right at home in this conversation with Joe.

2. A Cynical View of Love

"Lust with jealousy added" is Joe's cynical definition of love, and she claims to want nothing to do with it.

At one point, Joe admits to having sex with ten successive men in one day. She has a rule to not sleep with any man more than once. Joe maintains her power over them by telling them that she just had her first orgasm. She also tries not to see these men again. But that rule is broken in an affair with a married man. When his angry and out-of-control wife (Uma Thurman) tracks her husband down and spews her disgust and hatred for him with her three young sons witnessing the spectacle, Joe ends the affair.

The only other insight we have into Joe's exposure to love is her relationships to her mother (Connie Nielson) and father (Christian Slater). She never really connected with her aloof and envious mother who resented all the time her husband spent with his daughter. In several flashback scenes we witness the sensitivity he has for the natural world and his love of trees, which he passes on to Joe. In one of the most harrowing scenes of Nymphomaniac, she watches her father die in the terrible grip of delirium tremens.

3. The Perfect Listener

"There's nothing sexual about me," says Seligman who comes across as a good listener.

Seligman is a voracious reader, a student of human nature, and a natural born teacher. He demonstrates what it is like to be totally present while another person is telling the story of her life. Whereas Joe repeatedly puts herself down as a bad person who uses people, Seligman refuses to judge her and in a series of digressions, reveals his compassionate concern for her well-being. Be sure to catch his thoughts about Roman history, the Bible, Fibonacci numbers, Edgar Allen Poe, Thomas Mann, and Polyphony in the music of Bach and Beethoven. No wonder Justin Chang, a critic for Variety has compared von Trier's mixture of philosophical meditations and sexual escapades to the experience of reading Playboy magazine in the 1960s and 70s.

4. Loneliness as a Constant Companion

In addition to her negative feelings about herself, Joe admits having "loneliness as a constant companion."

Despite her cherished moments during childhood of sharing the beauty of nature with her father, Joe does not evidence any joy or delight in anything, and especially not in having sex with so many different men. Nor does she exhibit any playfulness in creatively seducing them. The only pleasure she seems to derive is the moment of orgasm and as we watch these couplings, we see how von Trier has created a character who makes her own path eschewing both romantic love and marriage.

But the price of such freedom is very high — she is a lonely soul and perhaps the only one who has ever managed to get close to her (besides her father) is the patient and nonjudgmental Seligman who yearns to hear more of her story. We wonder where Joe's sexual adventures will take her next as she ages and faces new challenges and dangers in Nymphomaniac Vol. II.