By now, Pedro Almodóvar’s signature style has become so iconic, his aesthetic so affecting, that, were he less generous, he could rest easy and stop creatively excavating his own demons, content to release beautifully shot, increasingly irrelevant films for the rest of his career. He seems able to compose haunting images in his sleep, his rarely off-key brand of camp-infused melodrama always mixed with just the right amount of authentic heart. This makes it all the more astonishing that Almodóvar’s latest masterpiece Pain and Glory takes all of these expected elements, infuses them with a disarmingly open-book, semi-autobiographical truthfulness, and shows this artist at the top of his game, reaching out for confession, connection, and healing.

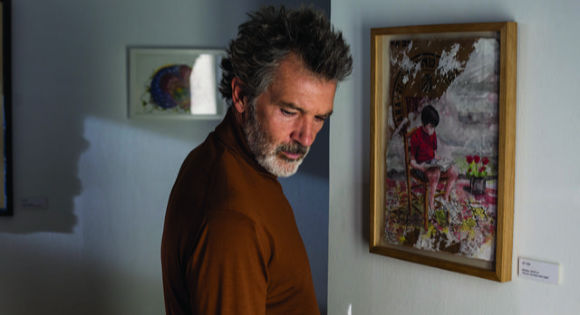

Salvador Mallo (Antonio Banderas) is an aging, queer film director, famous and infamous, adored and lonely, a slyly transparent stand-in for Almodóvar himself. Mallo is suffering, plagued by both physical pains, including debilitating backaches, migraines, and a strange choking affliction, and by painful creative blocks. How closely these afflictions come to Almodóvar’s actual experience is not the point here. Banderas, in a simultaneously grand and simple performance, is mesmerizingly relatable. Mallo’s pains are at once specific and universal, the artistic afflictions recognizable to any artist, and the physical pains recognizable even to those who have yet to endure quite as many hardships.

While the “pains” of the film’s title are apparent from the outset, the “glories” build slowly, coming together less as a cohesive narrative and more as a puzzle, its pieces fitting together with both ease and angst. As Mallo explores options for quieting his pain, two main timelines intersect, the first in present-day, as he rediscovers several important people from his career and lovelife, the second in his 1960s childhood, when his family moved to a Valencia village and he experienced his first, quietly traumatic sexual awakening.

In Mallo’s current reality, the past is still present, as he first reunites with Alberto (Asier Etxeandia), the complicated star of his first feature, Sabor, which is now considered a classic, though disagreements during filming decimated their partnership. Mallo then enjoys a chance encounter with his ex-lover Federico (Leonardo Sbaraglia), who is now a family man, having dated only women since his affair with Mallo. Drug dependence and its harmful and numbing effects on those in pain threads throughout both encounters, and the sharp memories of the destructive nature of addiction combines with some disconcertingly casual use of heroin to craft a complicated commentary on the fine line between use, abuse, sobriety, and escape.

The emotional rewards of these reunions might be enough on their own, but this is an Almodóvar creation, so they are given even deeper plangency by harmonizing with buried memories from Mallo’s childhood. In flashbacks to the 1960s, Mallo’s mother Jacinta (Penelope Cruz) is a centrifugal force in his childhood, a charismatic mix of comforting solace and bold inspiration. When Jacinta and young Mallo (Asier Flores) join Mallo’s father (Raúl Arévalo) in Valencia, both are disappointed by the austere conditions in which they are forced to live, hidden away in a dank, catacomb-like home inside a hill. But they make the most of it, and Mallo, a prodigy in reading and writing, takes on a local illiterate painter Eduardo (César Vicente) as a pupil. As a connection grows between the two, something blossoms inside young Mallo, and the result connects incontrovertibly to both the pains and the glories that will populate the rest of his life, both in love and art.

As these narratives weave together to construct the past and forge the future, Pain and Glory becomes a fugue of both regret and resurrection. The exhuming of the underlying causes of Mallo’s physical, emotional, and creative paralysis might be too bleak in the hands of another director, but finding the fabulous lightness and brightness within dramatic darkness is Almodóvar’s most exhilarating gift.

Pain and Glory never begs for pity for its main character; its storyteller is too self-reflective and forward-looking to get lost in desperation. Instead, the highs and lows of this imaginative journey move toward a horizon that suggests both resolve and reinvention. It’s a message that resonates far beyond this particular tale to inspire introspection for any willing to face both the agonies and the ecstasies of life and see the glorious landscape they create together.