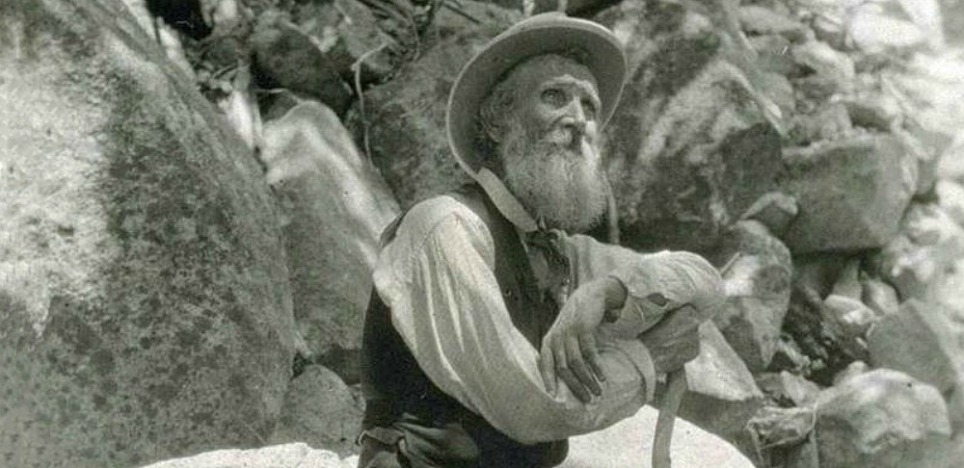

Born in Scotland in 1838, John Muir immigrated to the United States at eleven years old. He grew up roaming the woods and fields around his family home in Wisconsin before finding his way to California where his heart was captured by the Sierra Nevadas. A naturalist, botanist, and geologist (with specialized knowledge of glaciers), Muir spent his life exploring the Sierras, the Pacific Coast, and Alaska.

But saying that Muir "studied nature" is like saying that mystics study sacred texts: it tells us what he examined and leaves out how and to what end — and for Muir, these were everything. Whether he was writing about a bird, flower, field, or mountain, Muir observed all of nature deeply, seeing beyond color, shape, and size — beyond all classification — into its personality and immense power to inspire wonder and reverence. For Muir, the wilderness was a temple and sauntering around it a spiritual practice. With infectious enthusiasm, Muir wrote about the rivers of the Sierra Nevada as "his children" and about greeting boulders as fellow travelers, asking them “whence they came and whither they are going."

Muir’s kinship and intimacy with wildness nurtured his absolute devotion to protecting it. He is often called "The Father of Our National Park System" because of his advocacy on behalf of Yosemite, Sequoia, Mount Rainier, and Grand Canyon National Parks. The most rewarding culmination of his celebration and defense of wilderness, however, came in 1892 when the Sierra Club was founded and chose him as their first president.

Muir's legacy is the ongoing invitation for us to contemplate, appreciate, and protect the natural world around us.

To Name This Day:

Spiritual Practices

Spiritual Practices

Listen to One of Nature's Sermons: For Muir, nature was both church and sacred text. He wrote this about Yosemite Valley: “Nowhere will you see the majestic operations of nature more clearly revealed beside the frailest, most gentle and peaceful things. Nearly all the park is a profound solitude. Yet it is full of charming company, full of God’s thoughts, a place of peace and safety amid the most exalted grandeur and eager enthusiastic action, a new song, a place of beginnings abounding in first lessons on life, mountain-building, eternal, invincible, unbreakable order; with sermons in stones, storms, trees, flowers, and animals brimful of humanity.”

Find an animal or natural object in your environment and imagine what it would "preach." What tone are its words taking? What thought is God expressing through it?

Saunter: Asked how he felt about the word hike, Muir lit up with this response: "I don’t like either the word or the thing. People ought to saunter in the mountains — not hike! Do you know the origin of that word 'saunter?' It's a beautiful word. Away back in the Middle Ages people used to go on pilgrimages to the Holy Land, and when people in the villages through which they passed asked where they were going, they would reply, "A la sainte terre,' 'To the Holy Land.' And so they became known as sainte-terre-ers or saunterers. Now these mountains are our Holy Land, and we ought to saunter through them reverently, not 'hike' through them."

Muir’s account of saunter’s etymology invites us to connect going slow with experiencing the sacred. Today, "saunter" through some part of your routine that you normally "hike" through and notice how slowing down changes how you feel about the activity, your surroundings, and yourself.

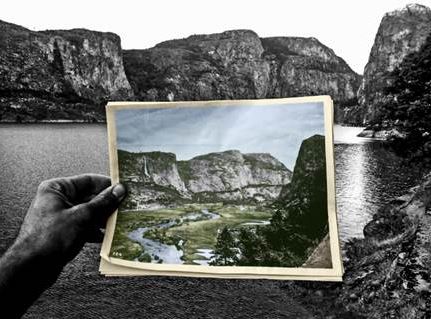

Make a Conservation Commitment: From 1901-1913, Muir and the Sierra Club led an effort to protect the Hetch Hetchy Valley from a proposed dam project that would provide electricity for San Francisco. They stirred up a massive public campaign; nonetheless, Congress approved the dam in 1913, and the city drowned this beautiful valley. This passage describing Hetch Hetchy is one example of the zeal with which Muir fought to protect our natural resources: "The sublime rocks of its walls seem to glow with life, whether leaning back in repose or standing erect in thoughtful attitudes, giving welcome to storms and calms alike, their brows in the sky, their feet set in the groves and gay flowery meadows, while birds, bees, and butterflies help the river and waterfalls to stir all the air into music — things frail and fleeting and types of permanence meeting here and blending, just as they do in Yosemite, to draw her lovers into close and confiding communion with her."

The Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park before and after the Raker Act was passed. Courtesy of Restore Hetch Hetchy.

Contemplate this before and after picture of Hetch Hetchy Valley. Then commit yourself to preserving something that you love.