Young Accio (Vittorio Emanuele Propizio) decides to enter seminary to escape his family. He feels like an outsider in his working-class family where all the attention and love are lavished on his older brother Manrico (Riccardo Scamarcio) and his sister Violetta (Alba Rohrwacher), a talented musician. But Accio is not cut out to be a man of cloth, and so he seeks out another way to fulfill his need to help others and make a solid contribution to society. He falls under the sway of Mario (Luca Zingaretti), a local Fascist leader who sees potential in the anger of this energetic teenager. When he is older, Accio (Elio Germano) joins the Fascist party and participates in a pilgrimage to Mussolini's grave.

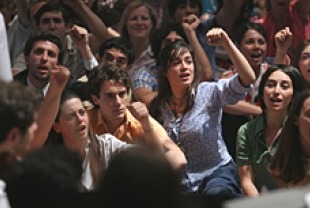

His brother Manrico has become a communist organizer at a local factory where he works with his father. He has begun dating Francesca (Diane Fleri) who, like many others, is impressed with his charisma. Accio develops a crush on her but chooses not to act on this attraction. Instead he begins an affair with Mario's middle-age wife who showers favors upon him as her young lover. But Accio's passion for Fascism dims when members of his group target Manrico and set his car on fire. When the Fascists attack the Marxists at a performance of Beethoven's Ode to Joy with a reworked libretto saluting their heroes, Accio is beaten up by his former comrades.

Director Daniele Luchetti makes the most of the dynamic screenplay by Sandro Petraglia and Stefano Rulli, the writers of The Best of Youth. Here the turbulent political options of the 1960s and 1970s play out in the city of Latina, a town created by Mussolini. Elio Germano, who exudes the same exuberance and spunk of Robert De Niro in some of his early films, plays Accio, the young man who allows outside forces and other people to determine his place in the world. He resents playing second-fiddle to his handsome and talented brother but is always there to demonstrate his love for him in small acts of service and gratitude.

Luchetti does a fine job depicting the politics of change which appeals to Accio and Manrico. They believe that their working-class parents deserve richer and fuller lives, and they are willing to do all they can to make this happen. As with the French film Blame It on Fidel, it is fascinating to watch politics take hold and offer the most viable path to personal transformation. It is a delight to see Accio try one thing after another as he struggles to define himself apart from his family. His quest for meaning is touching and a real pleasure to witness.