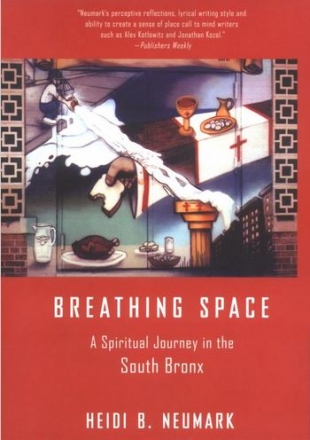

A memoir recommended for those who struggle to keep their faith in the midst of violence, suffering, injustice, and serious problems and who need to feel a sense of renewal and being refreshed.

Heidi Neumark served as pastor of Transfiguration Lutheran Church in the South Bronx for 19 years. She is a graduate of the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Philadelphia and is now a member of its Board of Trustees. An ecumenical leader and social activist, Neumark is committed to strengthening interdenominational relationships and urban neighborhoods. She is a founding member of South Bronx Churches, an ecumenical community organizing group, and the founder of Transfiguration Community Life Center, Inc., an organization providing after-school and job-training programs for youth, HIV and domestic violence education and support, and other services. She is also a founding member of the Inner City Guild.

Neumark was called to Transfiguration, an Hispanic and African-American congregation, in 1984. Getting ready to lead her first worship service, she saw under the altar a box of rat poison next to the box of communion wafers — a fitting introduction to the realities of a neighborhood that already had an international reputation as "an urban desert, a landscape of withered hopes, barren of economic vitality, battered by violence, fear and death." The statistics of the community were chilling to this white pastor: 60 percent of families on welfare, 80 percent of children living in poverty, 70 percent unemployment, only 3 percent of adults graduated from college, 80 percent of births to single mothers (and 20 percent of those teenagers), 20 percent of adults and teens testing positive for HIV, and 28 percent of all deaths annually due to drugs, AIDS or violence.

A theme that runs through this well-written and superbly pastoral memoir is the search for breathing space. Sewage treatment facilities, waste recycling plants, and incinerators burning the trash and hazardous hospital waste of New York City make it literally hard to breathe. Doctors link the many cases of childhood asthma in the Bronx to the garbage industry.

On another level, Neumark is constantly seeking out breathing space to process all of her experiences and to cope with the tragedies and the messes that rain down upon her and her congregation. In addition to her intensive labors in the parish and community, Neumark is raising two children. She is refreshed and renewed by the heroic men and women who struggle to keep the faith in the midst of gunfire, setbacks, and so much suffering. "To stand here is also to stand in the center of so much that is wounded and wrong in this nation and world, in a well of catastrophe that is, at the same time, a center which springs amazing grace."

In one passage, the author tests a spiritual practice that involves incorporating the distractions from prayer into the act itself. Only this time, the popping sound of bullets and automatic weapons proves too daunting a task for even a seasoned practitioner. Neumark speaks out against the curses of poverty, racism, sexism, and other demonic and divisive forces that divide people from each other. With true humility, she reveals what an honor it is to be allowed into people's lives, calling it "a sacred trust." She and the others leave their imprint on the South Bronx, renovating the church, getting more low-income housing, and improving the schools. Neumark states with conviction: "I have learned that grace cleaves to the depths, attends the losses and there slowly works her defiant transfiguration."