Thanks to Victor Hugo’s sweeping nineteenth century novel and its many adaptations, the Parisian suburb of Montfermeil is a near mythic place. Hugo chronicled in minute detail the rampant injustices that have historically run through the veins of the neighborhood. Now, director Ladj Ly has not so much adapted Les Misérables as used it as a launchpad from which to leap into a chaotic exhumation of the bodies, spirits, and communities that have for years fallen victim to systemic violence stemming from the most powerful among them.

In Hugo’s novel, small boy Gavroche serves as a symbol, both of scrappy innocence and of lamentable tragedy, and Ly’s film introduces its own version, naughty Issa (Issa Perica), first seen celebrating a French soccer win with mates and then finding himself at the center of an increasingly violent community breakdown, as one of his bouts of mischievous behavior grows beyond his control. Before too long, Issa will be seriously injured by one of the neighborhood’s police officers, and all hell will break loose.

The police officers in question spend their days bad-mouthing the inhabitants of Montfermeil in their patrol car, that is when they’re not actually threatening them on the streets. A newbie cop, Ruiz (Damien Bonnard), serves as the eyes and ears of the audience as he rides with his new, more acclimated partners: white and mercurial Chris (Alexis Manenti) and black and stoic Gwada (Djibril Zonga). Chris clearly has contempt for most everyone in Montfermeil: the kids, the Muslim Brotherhood, basically anyone of color who crosses his path. Gwada’s frequent silence makes him complicit to Chris’ outbursts, but it also suggests that his deferment to Chris’ outward-facing anger hides deeper resentment.

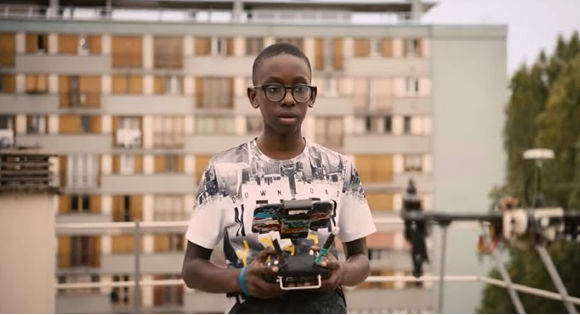

When Issa abducts a lion cub from a traveling Gypsy circus, the tough Roma owners vow vigilante justice and threaten the followers of Montfermeil’s ineffectual mayor (Steve Tientcheu). Chris sees this conflict as a chance to do what he loves to do: rough up some neighborhood kids. When this roughing up results in violence, and when that violence is filmed by a drone flown by quiet neighborhood kid, Buzz (Al-Hassan Ly), Chris shows even more of his true colors. He is far more concerned with tracking down the footage to save the cops from punishment than he is with making sure Issa is alright. As Ruiz attempts to get help for the boy while also trying not to set the volatile Chris off, Les Misérables takes on a tense urgency that can’t help but descend into collective madness.

The final third of the film balances this thriller-like atmosphere with gritty grace. Ly is not interested in violence for violence’s sake. He does not invite his audience to delight in chases, punches, and profanity. Every act of aggression, every nail-biting moment is meant to trouble, not tease. These characters are stand-ins for real people in real situations, and Ly wants onlookers to realize that there are real lives at stake. What might have been merely procedural in the hands of a more detached director becomes unavoidably personal in Ly’s care.

Les Misérables feels raw and rough because its reality is exactly that. The storytelling jumps, halts, and freezes because the lives it is depicting are stuck in continuous loops of retribution and revenge. The powerful governmental forces that patrol the streets reveal themselves to be as corrupt as any perceived criminal activity they purport to stamp out, and the most vulnerable, namely the young people at the center of all of this dealmaking and posturing, are left to bear the open wounds of a society unable to approach its historical and continuing systemic injustice with any ownership, accountability, or empathy.

With the powers-that-be violently flailing around them, these wounded young people take over the film’s closing scenes, exclaiming that they are watching, absorbing, waiting, and that they might just be gaining the strength to take issues into their own hands. What, the film asks, will these impressionable minds and hearts do with the world they see in front of them? Will they choose a new way, or will they simply recycle the power plays that have been modeled for them for millennia? The answer means everything for their (and our) future.