"There is no boundary between the sacred and the profane."

-- Thich Nhat Hahn

Jim Forest is an American writer, an Orthodox lay theologian, and author of three biographies of Catholic peacemakers, Dorothy Day, Thomas Merton, and Daniel Berrigan. Praying with Icons is a devotional classic, and we gave Writing Straight with Crooked Lines: A Memoir a book award in 2020 for its stories about the spiritual practices of' nonviolence, antiwar activism, and the mighty forces of courage, forgiveness, and loving one's enemies. Forest is profiled in our Living Spiritual Teachers Project. Also featured in the project is Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh.

Forest met Thich Nhat Hanh, then a young poet and Zen teacher, in Paris during the early 1970s. This Vietnamese refugee, sensing the American's irritation at having to take his turn at washing the dishes, asked him why he was doing them. The only answer Forest could come up with was, "You should wash the dishes to get them clean." Nhat Hanh replied, "No, you should wash the dishes to wash the dishes."

Forrest then admits that he has spent four decades mulling over Nhat Hahn's additional mystical suggestion:" You should wash each dish as if it were the baby Jesus." The author uses this teaching moment as a launch pad for further learning from Thay (as he is called by his students) over the next 46 years.

Among his speeches, peace proposals, poems, meditations. and prophetic words Forest has uncovered "the significance of insignificant activities": cutting vegetables, gardening, sweeping floors, waiting in line, etc. Other key teachings cover mindful breathing, the half-smile, killing the Buddha (discarding concepts and dogmas), hope as a lived experience, saying yes, service to others through engaged Buddhism, and the miracle of walking the earth. A recurrent theme is the importance of awakening oneself and others to the reality of suffering in the world: "Find ways to be with those who are suffering, including personal contact, visits, images, and sounds." A key concept is "interbeing":

"It means that each is in the other. Between us there is no border. In Buddhism we have a term that means interpenetration, but I prefer interbeing. Interpenetration presupposed that there is a border between us but that we can create a door. Inter being means the door is already there and was always there. We inter-are!"

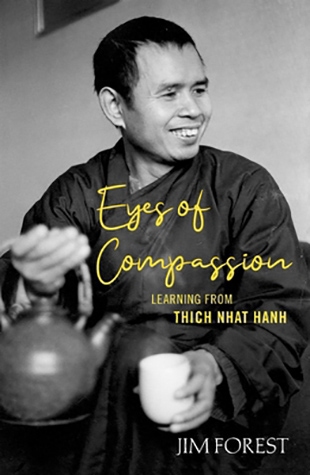

Two of the special qualities of Eyes of Compassion are Jim Forrest's wonderful collection of photographs of Thich Nhat Hahn, members of his communities, as well as reproductions of his calligraphy; they add a fresh dimension to this paperback. The other is the Zen Master's enactment of boundless compassion. Forest concludes:

"There is a lot to learn from Thay. Many would agree with me that he is one of the great teachers of the past hundred years. His voice will still be influencing people for many years to come."