I have spent a lot of time in mainland China over the years, teaching process philosophy to students young and old. The youngest are in kindergarten and the oldest are in their late eighties. I’ve been thirteen times in thirteen years.

One thing I’ve discovered in China is that philosophy cannot and need not be separated from everyday life and emotions. A philosophy quickly becomes irrelevant if it seems to be only a matter of the head not the heart, and if it lacks relevance to interactions with friends, family, and neighbors.

Thus I have appreciated aspects of process philosophy that are too often ignored by Western audiences: namely its emphasis on what Whitehead called subjective forms.

When we hear the word “form” we may initially think of objective forms: that is, the shapes and patterns of things we see in our eyes and entertain in our minds. The shapes of tables and chairs and trees and stars, for example. Subjective forms are different. They are the emotions we experience as we see with our eyes and entertain ideas in our minds. They are subjective, not objective. Awe, wonder, curiosity, fear, anxiety: these are subjective forms.

Chinese friends are especially interested in positive subjective forms: the emotions that can be part of a healthy life. Some speak of a life nurtured by positive subjective forms as spirituality. Of course the nurturing is itself an ongoing process, animated and guided by friends and family, hills and rivers, music and poems. “N” is for nurturing.

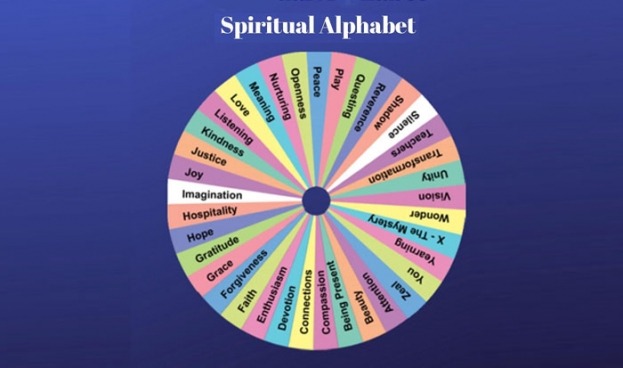

Knowing my context. I share the spiritual alphabet of Spirituality and Practice, using the diagram above. I introduce the letters in the alphabet as qualities of heart and mind and forms of relatedness that can help a person find a bit of happiness, given the circumstances of life. As I do so, I do not speak of “God” or “religion.” These words can evoke problematic feelings in some Chinese who have been conditioned to be resistant to both words. For many of them, rightly or wrongly, religion is too often superstitious and divisive; and God is an emperor in the sky, rightly rejected in the interests of freedom and human development.

Those of us who use the alphabet know that it is tremendously powerful as a way of naming and thus becoming mindful of some of the most important things in life: love and wonder, kindness and play, listening and beauty, for example.

And we also know that it can function as an invitation to imagine additional positive subjective forms that may not be obviously present in the alphabet. In China one important example of this is the letter C. In the alphabet it has two meanings: compassion and connection. Of course these are very important to all people, including Chinese. One reason people in China are drawn to process philosophy is that they believe it can encourage and support a deeply compassionate way of living in the world.

But one time, in exploring the letter C, a twenty-year old student said: “But what about curiosity. Can’t C stand for curiosity, too? For me this is one of the most important spiritual qualities available to us.”

His English name was Michael, and his specialty was physics. As Michael said this, I thought of the letter Q. “Q’ is for questing, and the pleasures of curiosity are indeed a form of questing. But I didn’t seem right in the moment to say to my friend “curiosity is a form of questing,” as if his insight gained validity only when subsumed in an already existing template. It seemed best to say: “You’re right! Add it!” I’m sure he did along with others in the group.

My own process musing these days, also a process hope, is that the spiritual alphabet can find its way into the hearts and minds of billions of Chinese who aren’t sure what they think about “religion” and “God” but sure know that they need and want wonder, imagination, love, listening, justice, and, yes, curiosity.

Truth be told, part of my own quest is to do my best to help people find the pleasure and depth of living life to its fullest, in relation to others, and in ways that are wise and compassionate and free. Perhaps you are on this quest, too. If so, we owe a tremendous debt of gratitude to the Brussats and to Spirituality and Practice for the myriad ways they have nurtured our quest, giving us vision for how life can best be lived. “V” is for vision and “N” is for nurturing. Let us say, in every way we can, thank you. “G” is for gratitude.

The Spiritual Alphabet in China

The Spiritual Alphabet in China