Ravishing black-and-white cinematography and the moving sounds of Polish folk music at first appear to be the main stars of Pawel Pawlikowski’s biting Cold War. Filmed in a throwback boxy ratio shaded in crisp grayscale and packed with vibrant melodies, this coyly ambiguous film might best be described as an epic romance. But its epicness is chopped up into unsettlingly short segments that take place over the course of decades, showing just enough to keep the audience as disoriented and yearning as its jaded protagonists.

As the tale kicks off in 1949, brooding conductor-pianist Wiktor (Tomasz Kot) is auditioning talent for a touring musical ensemble that will bring Poland’s rural musical sounds and movement to a country still smarting from the ravages of World War II. The moment brazen Zula (Joanna Kulig) opens her mouth to sing, Wiktor is enchanted. She might not have the crystal-clear pitch of some of the other ensemble members, but she has something ineffable that he can’t shake. Despite their age difference and much to the knowing amusement of Wiktor’s colleague Irena (Agata Kulesza), Wiktor and Zula begin an affair.

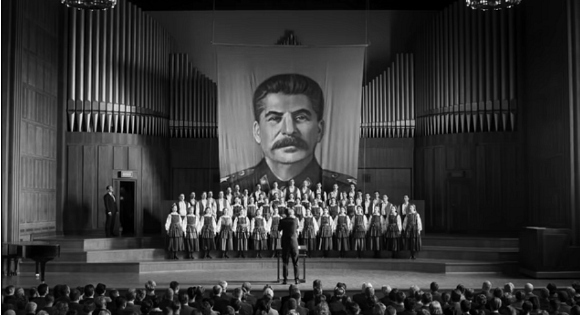

As the troupe begins to tour, Wiktor and Irena are pressured by the government to insert more inappropriately obvious Stalinist propaganda into their program. He grows weary of participating in such heavily compromised art. When he makes a daring decision to abandon the project, he assumes that Zula will flee with him, but when she does not show up at their meeting place, he sets off to Paris on his own.

Once this severing occurs, the remainder of the film comes in short spurts and fragments, as though the couple’s split has fractured any future possibility of clear cohesion or narrative flow. This is frustrating at times and audiences looking for consistently heart-swelling drama will be left wanting. Instead, the film slowly dissolves into increasingly enigmatic planned and chance meetings over the ensuing decades. The passion that once held the couple in thrall gives way to a codependency that seems more compulsory than loving. The cumulative effect of these brief encounters forces the audience to follow feelings instead of seeking clarity, as do the lovers themselves.

As years go by and the pair continues to meet up and break apart, the story’s splintered style becomes its most potent aspect, inviting viewers into a visceral understanding of the couple’s doomed dance of push-and-pull. Supplementing this tricky formal experiment with soulful authenticity are the performances of the two leads. Both actors are consistently committed to showing the depths churning beneath their characters’ icy surfaces, and their transformations from scene to scene are made even more thrilling by the absence of straightforward character arcs.

Throughout, music remains the only constant comfort. Zula gains confidence as a charismatic artist in her own right, while Wiktor channels his fevered frustration into sweaty jazz. In the magnetism of their stage performances, their common disgruntlement warms, thawing the frigidity of their increasingly fraught scenes with one another.

Cold War gives us a lovers’ journey as haunted and haunting as the history of a continent frozen between the utopian vision of what can be and the frustrating reality of what is. It starkly reveals how yearning can sustain a flame between two people, even as time, space, and politics conspire to numb their steamy, creative spirits.