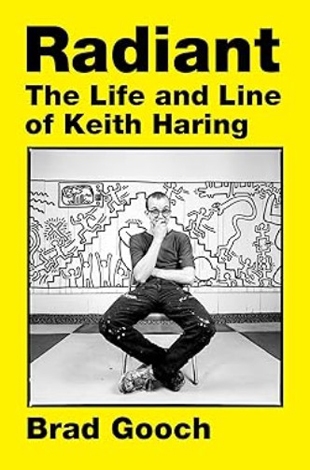

This biography of American pop culture icon and artist Keith Haring is inspiring, even if you don’t remember who Haring was. He shined brightly but briefly in the 1980s, predominantly from the East Village of New York City, as a modern cartoon and graffiti artist of the people.

Haring got his start by tagging dumpsters, police barricades, subway maps, and the like with images that were quickly favored and loved by ordinary New Yorkers: barking dogs, nuclear reactors, and most of all, crawling babies. The crawling baby — which is today available on t-shirts, coffee mugs, and posters, like any number of Andy Warhol soup cans — was usually created with a thick black marker drawn in a single continuous line.

That baby was first made famous in an article in ArtForum, which called the figure, “The Radiant Child.” This is the inspiration for the title of Gooch’s biography. Haring died at the age of 31, in 1990, one of the many casualties of the AIDS epidemic in America.

Gooch is a talented biographer, whose earlier study of the Catholic novelist Flannery O’Connor was a New York Times best-seller. Most compelling about this study of Haring — amply illustrated with examples of the artist’s work and photographs of him with other icons of the eighties including Michael Jackson, Dolly Parton, Grace Jones, and Boy George — is how Gooch lifts up and demonstrates his hopeful humanism.

“Haring’s humanism, unusual for the period [a generally “dark” time in New York City], was unironic,” the biographer explains early on.

Haring’s early examples of drawing came from his father, a talented amateur cartoonist, as well as Dr. Seuss and later, Alice in Wonderland. He created art, and sought to do so, that would appeal to everybody. “Haring had a knack in his public art for making the overlooked visible,” writes Gooch. Haring’s materials included Post-it Notes (stuck on staircases), and chalk (drawn on subway panels — see the excerpt accompanying this review).

A youthful period of years spent among “Jesus freak” hippies was intertwined with experimental drug use and explorations of his sexuality. Then, art school in Pittsburgh, and on to life in Manhattan, where in 1980 Keith’s art took a distinctively political turn during the presidential campaigns of Ronald Reagan and Jimmy Carter. The sense is that it all went by much too quickly.

In 1988, when so many of his friends had died or were dying of AIDS, Haring also had his diagnosis but continued to celebrate life. This is expressed beautifully in the latter chapters of this compelling biography and on into the account of Haring’s funeral service, which was unusually full of children who had each been mentored by the artist.