"Alchemy was the medieval analogue for the process of transformation, and Jung studied it at length. Gustafson draws on Jung's study of alchemy to make the argument that the development of devotion to the Madonna at Einsiedeln parallels the process of alchemy. A striking emphasis is placed on darkness or blackness as the initial stage of the alchemical work. And that blackness, Gustafson notes, in medieval times was called the 'Raven.' The legend of Meinrad and the ravens takes on another layer of meaning.

"The blackness with which the alchemical process begins is also known as the nigredo. It carries many levels of meaning. The nigredo is a symbol full of ambiguities. According to Jung, the 'crow or raven' or 'raven's head' is the traditional name for the nigredo. 'To nourish the ravens is to nourish the contents of the dark experiences of one's psyche and life,' Gustafson tells us. The possibility of wisdom and insight comes from including the dark, chthonic secrets of life. Citing Jung he points out that 'it is of the essence of the transforming substance to be on the one hand, extremely common, even contemptible . . . but on the other hand, to mean something of great value, not to say divine. For the transformation leads from the depths to the heights, from the bestially archaic and infantile to the mystical homo maximus.'

"Jung's description of this essence reminds me of addiction. The disease draws one into an increasing loss of self-respect, to the point where, at bottom, it is felt that hardly anyone could be more 'contemptible' than oneself. Yet in recovery, the very wound that drains one's life is the greatest source of healing and transformation, 'from the depths to the heights . . .'

"Jung's use of the word 'mystical' fits precisely my own experience. One has a chronic, medically verified disease and yet there is no known medical cure, nor has there ever been. The surest, most demonstrably consistent recovery, year after year, comes through abstinence combined with abandoning oneself to a life of the spirit. The body recovers, visibly and dramatically, physical health returns, through commitment to the spirit, however one might define that for oneself. The mystical experience of the sages and saints, no separation between oneself and the divine, or in Buddhist terms, the experience of nonduality, can come through the back door of addiction turned inside out by the recovery process.

"Many people are able to stop drinking or using drugs initially, but the harder issue is to 'stay stopped' and to transform one's life into a source of joy and pleasure rather than remaining in the painful state that fueled the need for the anesthesia of choice.

"This is the great alchemical formula; it takes spirit to cure spirit, Jung said. The phrase comes back to me again.

" 'Self-knowledge is an adventure that carries us unexpectedly far and deep . . . (it) can cause a good deal of confusion and mental darkness. . . . For this reason alone, we can understand why the alchemists called their nigredo melancholia, "a black blacker than black," night, an affliction of the soul, confusion . . . or, more pointedly, the "black raven," ' Gustafson tells us, drawing again on Jung.

"The construction of the chapel of the Black Madonna within the larger church of the monastery at Einsiedeln directly over Meinrad's cell and place of death takes on a larger resonance, and points not only to an event but to the alchemical process itself. The Black Madonna of Einsiedeln grew out of Meinrad's decision to live with the 'ravens,' to pursue a deeper meaning in life, to go 'the way of the nigredo, the Finsterwald,' to inhabit his own dark places.

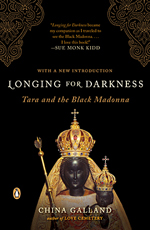

"To say that one is 'longing for darkness' is to say that one longs for transformation, for a darkness that brings balance, wholeness, integration, wisdom, insight, I now realize. For so long I didn't know what I meant when I said that, when I felt it — a longing for darkness. I remember standing in front of that statue of Kali at Varanasi and thinking of this Madonna at Einsiedeln. Now I find not only the Madonna but the beginning of words to name that longing and desire.

"Late one night over coffee, when I said that I was longing for darkness, a friend said, 'Watch out! It's dangerous to say that. You don't know what you are calling to yourself.'

"The association of the word 'darkness' with something negative, with evil, is precisely the problem I am naming. That kind of association is one of the cornerstones of racism. Racism is evil, not darkness. There is a redeeming darkness and this is what I seek.

"Seeing the Madonna of Einsiedeln proved to me that the longing for darkness is a deeply felt human need that cuts across, goes beyond, and at the same time includes issues of ethnicity. This is a multivalent darkness. This is the darkness of ancient wisdom, of people of color, of space, of the womb, of the earth, of the unknown, of sorrow, of the imagination, the darkness of death, of the human heart, of the unconscious, of the darkness beyond light, of matter, of the descent, of the body, of the shadow of the Most High.

"Like light, darkness has a wide range of symbolic meanings. The color black can signify the stage just before enlightenment in Tibetan Buddhism — imminence; space; burning; the final stage of the soul's journey to beatitude in a Sufi tradition; wisdom; fertility in Old Europe; purity in a Turkish tradition; mourning in the West; and the first step in the medieval alchemical process, the nigredo."