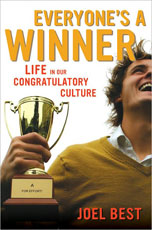

"We pass out praise and superlatives freely. Americans have a global reputation for being full of ourselves. We chant, 'U.S.A. — Number One! U.S.A. — Number One!' We confidently describe our country as the world's greatest, its sole superpower. But self-congratulation is far more than a matter of national pride. It is a theme that runs throughout our contemporary society.

"The kudos begin early. These days, completing elementary school, kindergarten, even preschool may involve a graduation ceremony, complete with caps and gowns. Many children receive a trophy each time they participate in an organized sports program, beginning with kindergarten soccer or T-ball, so that lots of third graders have already accumulated a dresser-top full of athletic trophies. Many elementary school classrooms anoint a 'Student of the Week.' Experts justify this praise by arguing that children benefit from encouragement, positive reinforcement, or 'warm fuzzies.' As the commentator Michael Barone sees it: 'From ages six to eighteen Americans live mostly in what in I call Soft America — the parts of our country where there is little competition and accountability. . . . Soft America coddles: our schools, seeking to instill self-esteem, ban tag and dodgeball, and promote just about anyone who shows up.

"But children aren't the only beneficiaries of our self-congratulatory culture. Awards, prizes, and honors go to adults — and to companies, communities, and other organizations — in ever-increasing numbers. It is remarkable how much of our news coverage concerns Nobel Prizes, Academy Awards, and other designations of excellence. And, at the end of life, obituaries often highlight the deceased's honors ('Bancroft Dies at 73. Won Oscar, Emmy, Tony'). Congratulatory culture extends nearly from the cradle to the grave.

"This isn't how we like to think of ourselves. Michael Barone insists: 'From ages eighteen to thirty Americans live mostly in Hard America — the parts of American life subject to competition and accountability. . . . Hard America plays for keeps: the private sector fires people when profits fall, and the military trains under live fire.' The imagined world of Hard America is governed by impersonal market forces, and rewards don't come easily. There is stiff competition, and only the best survive and thrive. This vision begins American history with no-nonsense Puritans whose God expected them to work hard and receive their rewards in heaven. People were to live steady lives and gain the quiet admiration of others for their steadfast characters. Pride was one of the seven deadly sins. In this view, our contemporary readiness to praise — and to celebrate our own (or at least our middle schoolers') accomplishments — seems to be something new.

"So what's going on? Why are contemporary Americans so ready to pass out prizes and congratulate one another on their wonderfulness? What are the consequences of this self-congratulatory culture?"