"These days, love and charity are — or can be — earthly, mundane phenomena: what we do and how we act in our everyday lives toward one another and ourselves, whether we are religious or not. Dogs lead by example. Watching Pransky jump in bed with a nursing home resident or put her head in someone's lap, I could see that the love she was sharing was both simple and profound. It was kindness, compassion, and affection in a single gesture; it was blind; it asked for nothing in return. When the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer wrote about loving-kindness, it was with a fair amount of cynicism. People were often good to one another because it suited them, he suggested. Love was a kind of ego boost. For loving-kindness to be real, for it to have moral value, he observed, it must be practiced with consideration 'of the other's distress alone.' In this was an echo of Buddhism's Four Immeasurables, in which the first, love, was simply wanting others to be happy. Could this be why people trusted and accepted dog love, even from a dog they did not know? Could this be why, when those researchers asked people to show where the people and dogs in their life stood in relation to themselves, the dogs were closer? Dog love was morally uncompromised. It was uncomplicated. It was trustworthy. Dog love — not the love for dogs in general or any one dog specifically, but the love dogs show us — matched Aristotle's idea of 'philia,' the place where friendship merged with love or, as he put it, 'wanting for someone what one thinks good, for his sake and not for one's own, and being inclined, so far as one can, to do such things for him.' On the other hand, if there was a dog biscuit in the offing, all the better."

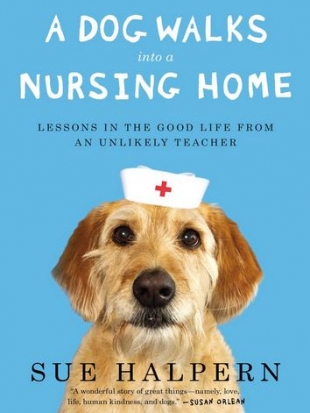

A Dog Walks into a Nursing Home Lessons in the Good Life from an Unlikely Teacher

Sue Halpern on how the sharing of love by dogs is keen and true.