“The arc of Thoreau’s recovery, from John’s [his brother’s] death in January 1842 to the publication of 'The Natural History of Massachusetts' in the 'Dial' for July 1842, spans just six months and resulted in neither a change of subject nor profession. Instead, the process involved a deepening, a rethinking and revalidation of an approach to nature that Thoreau had already held in a general way before John’s death. But what had been a more or less conventional romantic approach to nature quickly became, after John’s death, a profoundly felt emotional acceptance — not just an intellectual assent — of death as an inescapable part of living, and an acceptance that at some level, there is no death. The very process of decay is a life process. The consequences of this view — of believing, not just mouthing — is to understand and accept a disindividualized view of life. The individual may die, but the materials that make up the individual do not. They are subsumed into new forms and so live on. This view, if one can grasp and hold it, means that in a general or communal sense, there is no death. This conviction, once firmly accepted, is, paradoxically, a powerful force for individual resilience. The wide-awake individual now knows that his or her resilience is not idiosyncratic but something held in common with all other people and all other forms of life, and derives its power from the very fact that it is common.”

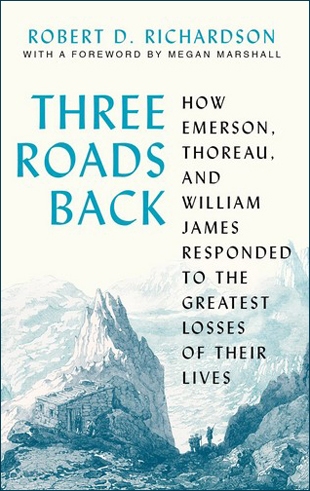

Published by Princeton University Press and reprinted here by permission