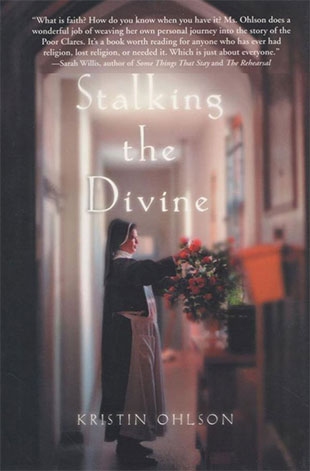

Kristin Ohlson, a freelance journalist, essayist, and fiction writer, lives in Cleveland, Ohio. One Christmas morning, she decides to go to church and ends up at St. Paul Shrine, an inner-city congregation with 50 members. Ohlson, a lapsed Catholic, sits in the pew and suddenly finds odd feelings and thoughts going through her body and mind: "On this lonely day, I wanted to be surrounded by the rituals of the faith I had grown up with and then bolted from as a teenager. I wanted to be in the midst of people who had gathered to share a belief in something greater than the assorted daily struggles of their lives. I wanted to sing and bow and kneel and pray along with them. Even if I didn't share their convictions, I thought it possible to be infected by their fervor, to pick up a tiny germ of faith that might quicken and grow. . . . During most of my life I had considered faith a kind of sickness, something that softened the brain and allowed the soothing delusion of divine power. Now I wanted faith, but I wasn't sure if I hadn't inoculated myself against it for good."

Not quite knowing why, Ohlson is drawn to find out more about a group of nuns cloistered in the monastery at the back of the church. There are only 16 of them, and they are part of the religious order called the Poor Clares of Perpetual Adoration. They pray all day and night. Sometimes they climb up on the roof of the monastery at night to watch over Cleveland: "There they prayed for the city, noting the twinkle of each distant light and the wavering lines of streets that radiated from downtown into the darkness beyond." Over a three-year period, Ohlson talks to the nuns, writes an article about them for a newspaper, and in the process is compelled to renew her faith in God, start up her own prayer life, and draw closer to others through compassion.

The author is inspired by these Christian women and their commitment to the contemplative life with its long periods of silence. The Poor Clares meet as a group five times a day to chant the Liturgy of the Hours but then individually and in pairs throughout the rest of the day and night pray in front of the Blessed Sacrament. They share with Ohlson their delight in this constant adoration of God and the way their intercessory prayers link them with others. The author tries a 12-hour prayer vigil through the night and comes away with even more respect for the rigors of the Poor Clares' devotional life.

Reading this spiritual account, we were deeply moved by this practice of holding the world in prayer. Ohlson visits her sick mother in California and physically senses the prayers of the Poor Clares back in the Midwest. Here tending to the devotional life is presented as a path into faith.