In a Hirokazu Kore-eda film, authentic connection is everything. This most open-hearted of filmmakers always appears to do very little. Content to rely on steady observation, while eschewing stylistic fireworks, Kore-eda has quite simply crafted some of the most affecting onscreen relationships in recent memory. With decades of consistent portraits of both biological and makeshift families culminating in Shoplifters, the winner of the Palme D’or at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival, it should come as no surprise that this most consummate of auteurs now has his pick of collaborative opportunities. His latest offering, starring two giants of French film and his first made outside his native Japan, seems both a strange and obvious next step.

While Shoplifters explored Kore-eda’s growing interest in the more invisible members of society (the poor, the working class, the lost, the forgotten), The Truth appears to take a 180-degree turn, focusing on lives that shine in the spotlight, most specifically the artists in the movie business who make entertainments eagerly consumed by obsessed audiences. But this would not be a Kore-eda creation without a healthy dissection of the demands that both family and societal obligations place on human beings, especially women. Ultimately, even though The Truth focuses on distinctly bourgeois French characters, common Kore-eda themes found in his previous explorations of the underclass are threaded throughout. The result is a subtle, meandering film that may at first appear to be not much more than a slight French confection, but upon further reflection turns out to have ample spiritual layers.

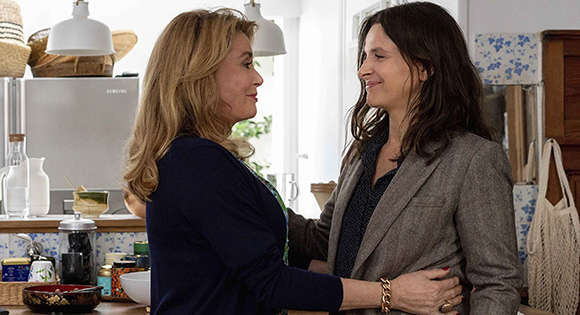

Of course, casting two French powerhouse actresses in their first onscreen relationship sets The Truth on a very specific course from the outset. Catherine Deneuve and Juliette Binoche are far too celebrated to not bring a sense of grandeur and expectation to any film they inhabit. And the fact that they are playing a mother and daughter whose lives have been dedicated to and stunted by moviemaking, brings a meta quality to the proceedings that might at first feel mightily trivial when compared to Kore-eda’s more searing works of social commentary. But Kore-eda, Deneuve, and Binoche are interested in more than a throwaway insider exposé.

Deneuve is Fabienne Dangeville, decades into her career, both beloved and aging, on the cusp of becoming invisible in the way that so many older women do in a beauty-obsessed industry. Binoche is Lumir, Fabienne’s put-upon screenwriter daughter, who has escaped to the United States and married struggling actor Hank (Ethan Hawke), but has recently returned to France to celebrate the release of her mother’s new memoir, coyly titled The Truth. It’s the perfect setup for two real-life stars to chew the scenery and grab a paycheck in a forgettable film that folks will flock to see. But under the precise, penetrating guidance of Kore-eda, something else emerges: a quiet, but scalding, indictment of authenticity itself.

Upon reading Fabienne’s book, Lumir rediscovers something she’s always known: that her mother is only concerned with truthfulness onscreen, while offscreen, she manufactures memories filled with fabrications that will please her fans and maintain her legacy. This new dose of indignity gnaws at Lumir’s desperate desire for a real connection with her mother, a connection she did feel with her mother’s best friend Sarah, a feted actress herself until she tragically died in Lumir’s youth. Now, Fabienne is filming a new movie with (and is more than a little jealous of) hot young actress Manon (Manon Clavel), whom everyone compares to the dearly missed Sarah. The layers of identity, self-delusion, disappointment, and disconnect begin to pile up and simmer, waiting to explode.

But the explosion is a gentle one, since Kore-eda is far more dedicated to portraying genuine human emotion than he is to shooting off pyrotechnics for the sake of entertainment. Characters reveal unexpected layers, mostly through throwaway gestures and casually dropped lines. Fabienne, self-absorbed and narcissistic, articulates strangely cutting wisdom. Lumir, frustrated and neglected, shows her own reliance on inauthentic self-preservation. And, along the way, the fractured relationships that each woman has with the others in their lives show a through line arcing back to their own tentative love.

Like its characters, The Truth never completely reveals its hand. It’s deliciously acted, but its stars always seem to be holding back a bit, perfectly supplementing Kore-eda’s plainspoken but still evasive screenplay. The questions left for viewers to ponder are as simple and profound as they come: What do we truthfully owe one another? Is true connection really possible, especially in a world where finding the right nuance for a line and the best angle for a shot is so celebrated? And, really, who are we when we are constantly worried about how others are perceiving us? Films try to show us perfectly honed scenes and stories, but since life itself is much messier, can we admit that vulnerable honesty and self-reflection get us much closer to connection than perfect articulation ever could?