In late 1938, Nicholas ("Nicky") Winton, a 29-year-old Englishman, was invited by a friend to Prague, Czechoslovakia, where some 250,000 refugees from Nazi persecution were struggling to survive. Upon learning that the British government would take in refugee youngsters up to age 17 if they had a host family with whom to stay and enough money for a return ticket, Winton began a complicated dance of making it possible for children to take this difficult journey to safety. One of the children he helped was Veruska ("Vera") Diamantova.

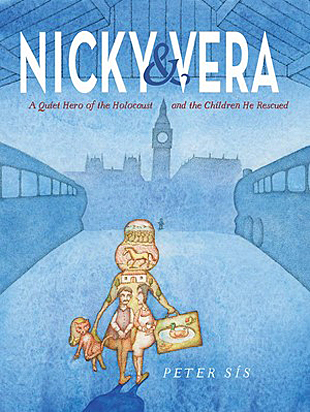

In Nicky & Vera, Peter Sis tells and illustrates the stories of these two, calling them by their nicknames and alternating from one to the other until late in life when they finally meet. Sis masterfully meets both child and adult readers at their respective eye levels. Children see Nicky on the playground of his alternative elementary school, imagining himself as a knight fighting dragons; adults will likely notice the inscription on his shield: "Put needs of others first." Children see Vera in her little town near Prague giving an extra pair of her shoes to a barefoot refugee in her class; adults notice the almost infinitesimal approaching line of tanks on the far horizon.

By emphasizing joy and passion — such as Nicky with his love of fencing and Vera with her love of her town's cats — Sis makes the story about robust living rather than simply about impending doom. For doom is, as any student of history knows, rapidly approaching Vera's town, all of Czechoslovakia, and much more beyond. But what a child understands is that at an urgent moment, the main characters and their loved ones do what is needed to preserve life to the best of their ability.

Nicky sets up an office in a hotel in Prague, where he can make a list of children who need to be evacuated, get their photos, and find families with whom to connect them — all despite the danger from spies. He applies for visas and makes travel arrangements, often at his own expense. Meanwhile, Vera's family collects extra food and clothing "just in case." When the heartbreaking time comes in which Vera must part with her family, we see their strength most of all: Her father gives her a diary so she can record her memories; she says goodbye to her cousins, coming on a later train; and she tries not to cry, as she shares with other fleeing children stories of the lives they left behind.

Sis gives us a two-page spread showing all eight trains that carried 669 children to safety in London thanks to Nicky's work. He does not spare us the sad news that — as a result of closed border crossings — the ninth train, holding 250 children, including Vera's cousins, never leaves for London. He sensitively explains no more. That way, readers who want to know more can ask an adult and get age-appropriate answers about what eventually happened to those remaining children.

If there's anything more extraordinary than Nicky's protecting hundreds of young lives, it is the way he never drew attention to this accomplishment. Only years later, when his wife found related documents in their attic, did his story come out, allowing for a profoundly moving reunion with the now-grown children, Vera included.

While the book's official reading age designation is six to eight years, it will readily captivate those older than eight as well, for it reminds us to be true to our convictions. As Nicky said, "If something is not impossible, then there must be a way to do it."

Watch a BBC video of Nicholas Winton's reunion with some of the people who owe him their lives:

How true to his humility that he would say, "I never thought what I did 70 years ago was going to have such a big impact, as apparently it has. And if it has now got a story which helps people to live for the future, well, that would be an added bonus."