This book is like a magnet, and it's hard to say what draws you first. Maybe it's the unusual title? Who are the flower-song people?

They are the Nahuas, the indigenous people of Mexico, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua. In her author's note, debut picture-book writer Gloria Amescua explains that they called poetry xochicuicatl, "the flower and the song," which she shortens to "flower-song" to represent the Nahua spirit.

Even though the book contains careful historical research, it does read like poetry. It centers around the true story of a girl who in the opening pages gazes up at "the stars sprinkling the hammock of the sky."

"She was Luz Jiménez

child of the flower-song people,

the powerful Aztecs,

who called themselves Nahua —

who lost their land, but who did not disappear."

Immersed in her traditional culture, preserved in spite of Spanish colonization, Luz cultivates a profound understanding of "how the Nahua suffered — and sweet joy — how her people survived." She listens to elders repeat her grandfathers' grandfathers' stories, learns to twist yarn with her toes, studies weaving and herbal medicine, and much more. She is also eager to attend school and learn from Spanish textbooks, though, and to learn skills like dressmaking and drawing.

When she turns 13, Luz's blossoming dreams of becoming a teacher nearly die. Her father is killed in the Mexican Revolution, and the school at which she excelled is reduced to rubble. These changes cause her family to move to the city. There Luz opens to new ways of being, modeling for artists like Diega Rivera, Fernando Leal, Tina Modotti, and Jean Charlot who honor the native people colonized by the Spanish. She then becomes friends with scholars who want to learn Nahua language and culture, and her desire to teach is fulfilled as she guides anthropologists and artists to understand the life of her people.

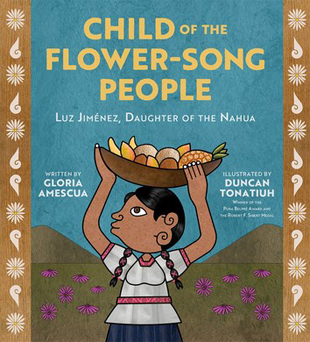

The magnetic attraction of this book surely also comes from the striking Pre-Columbian inspiration in the art by Duncan Tonatiuh. Tonatiuh, whose numerous accolades include the Pura Belpré Award and the Robert F. Sibert Medal, aims to create images that honor the past yet are fresh and relevant, something he achieves masterfully in everything from Luz cradling a wild flower in her hands to her leading a tour of native festival dances. Several of the pictures pay homage to the art for which Luz modeled.

Most of all, the book's draw may be Luz Jiménez herself who — to give just one example of reasons we should all have heard of her — appears in at least three of Diego Rivera's murals, one of them the famous Tlatelolco market scene. Even more importantly, she carried the language and culture of her people into the 20th century and beyond, such as by hosting the First Aztec Congress (1940) which determined how the written Nahuatl language should appear.

A timeline of her life, a glossary, and a select bibliography round out this fascinating book which introduces readers ages six to ten to a woman through whom the world came to know "the spirit of Mexico."