Some people read the Gospels to understand doctrine or confirm their cultural perspective; others, to understand how to live. Clarence Jordan was one of the people who saw in the Gospels a model for how Christians are called to act in the world, and he became a model and a mentor to many others.

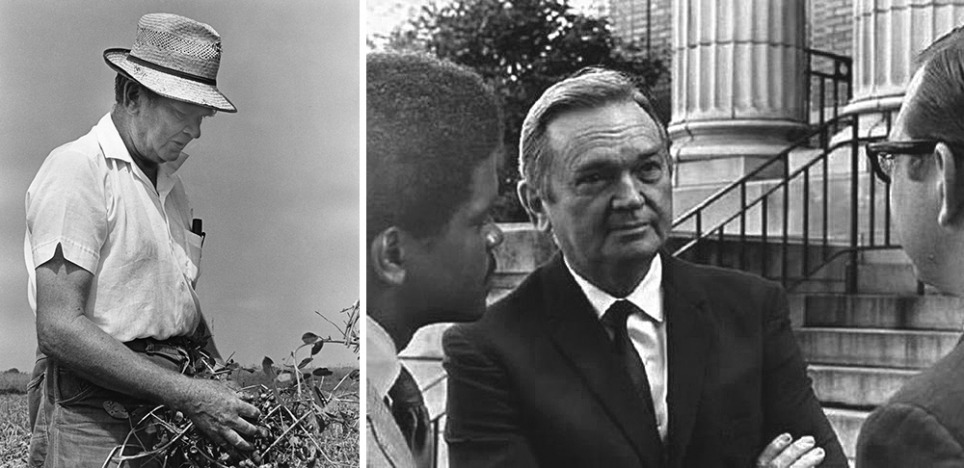

Jordan was born on July 29, 1912 in Talbotton, Georgia. Even when he was growing up in the Baptist church, he couldn't understand how Christians could abide by racial segregation. He chose to study agriculture so that he could help sharecroppers learn scientific farming techniques, but changed course when he felt called to the ministry. He served as pastor of three rural churches and then, wanting to integrate these two callings, he moved with his wife Florence, their young children, and a Baptist missionary couple to a red-dirt acreage near Americus, Georgia. There they established Koinonia Farm (from a Greek word for "fellowship") a place where they envisioned black and white people could work together. They began with these principles:

All people are related in God’s eyes.

Live in accordance with Christ’s love.

Common ownership, with distribution according to first-century Christian principles based on need, not profit.

The Jordons stuck with their dedication to this vision even when it meant gunshots and boycotts of their farm produce from neighbors who despised them. Meanwhile, Clarence was doing some remarkable writing. He is perhaps best known for his Cotton Patch Gospels, Epistles, and other Cotton Patch books, in which he uses down-to-earth and surprising words and imagery to make New Testament texts come alive.

Koinonia is still going strong as a place of peace and unity. In 1968, together with Millard and Linda Fuller, the Jordans launched Koinonia Partners, which included a building program that eventually evolved into Habitat for Humanity. Volunteers worked side-by-side with future homeowners to build simple, decent, affordable homes.

On October 29, 1969, at the age of 57, Clarence Jordan died in his writing shack at the farm. According to the Georgia Encyclopedia, "the local coroner refused to come to the farm to pronounce him dead." We can only imagine the grand welcome in heaven, though, for someone who understood and lived by what Jesus demonstrated to us all.

To Name This Day:

Quotes

Quotes

Choose one of these quotes today and consider how to incorporate its wisdom into your life, in honor of Clarence and Florence Jordan:

“Faith is not belief in spite of evidence but a life in scorn of the consequences.”

— Clarence Jordan, The Substance of Faith: And Other Cotton Patch Sermons

“God is not a celestial prison warden jangling the keys on a bunch of lifers — he's a shepherd seeking for sheep, a woman searching for coins, a father waiting for his son.”

— Clarence Jordan, The Substance of Faith: And Other Cotton Patch Sermons

“Even though people about us choose the path of hate and violence and warfare and greed and prejudice, we who are Christ's body must throw off these poisons and let love permeate and cleanse every tissue and cell. Nor are we to allow ourselves to become easily discouraged when love is not always obviously successful or pleasant. Love never quits, even when an enemy has hit you on the right cheek and you have turned the other, and he's also hit that.”

— Clarence Jordan, The Substance of Faith: And Other Cotton Patch Sermons

"A distinguished professor once came to the farm while Clarence was working on a tractor. The man said, 'I wish to speak to Dr. Jordan.' Clarence wiped off a greasy hand, extended it, and said, 'I am he.' The man responded, 'No, I wish to speak to Dr. Clarence Jordan.' Clarence insisted that he was the one the man was looking for. After repeating his request, the professor finally got in his car and left. A few days later Clarence received a letter from the man, expressing that he was infuriated with the impudent help that Dr. Jordan managed to keep around."

— Joyce Hollyday in Sojourners, December 1979, Vol. 8, no. 12

Spiritual Practice

Spiritual Practice

Drawing from Joyce Hollyday's biographical essay in Clarence Jordan: Essential Writings, Plough Quarterly shares this story:

"The Sermon on the Mount continued to fuel Clarence’s message. From those chapters of the Gospel of Matthew, which he referred to as 'the platform of the God Movement,' he drew a profound critique of materialism, ecclesiasticism, and militarism, which he saw as the most powerful forces competing for people’s minds and hearts. He had no respect for ostentatious Christianity or the self-righteous religiosity so rampant in Southern Christian culture. 'That cross alone cost us ten thousand dollars,' bragged a pastor as he gave Clarence a tour of his church.

" 'The time was you could get them for nothing,' Clarence shot back."

A life like Clarence Jordan's gives him the authority to pop out with a quip like that: funny, incriminating, yet somehow not even judgmental. Most of us stand to learn a lot from him.

Today, make a list of five or ten possessions that you most associate with who you are. These could be anything: a potter's wheel, a car, a ring, an heirloom pitcher, a piano, a computer, a holy statue, a book. Write them down the left side of a page, and create two columns across the top. In one column ("Enhances"), write the way that a given possession enhances your ability to carry forward your vision in life. In another column ("Holds Back"), write any ways in which the possession holds you back. Spend a few minutes noticing anything interesting you can learn from the list about how you want to act towards your belongings.