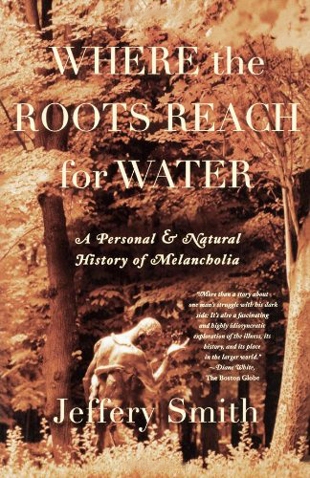

Jeffery Smith, in a brilliant account of his battles with depression, also writes about the devotional aspect of walking.

"As a child I had walked constantly and joyfully; even when all my classmates were driving to school I walked. This befuddled the menfolk in my car-obsessed home region; I went for nearly two full years after my sixteenth birthday without obtaining a license to drive. That March I took up regular walking again.

"It was another of those times when things seemed to converge: I got to reading about walking, and in Bruce Chatwin's Songlines, I read that for centuries a pilgrimage or walkabout was thought highly specific for melancholia. And I could see that: it had always made for a useful balance for me: when walking I could ruminate, could recite or sing; but any preoccupations, self-absorptions, flights into the abstract, could be shattered in an instant: by the play of light across a meadow, by a mound of carpenter ants along the roadside, by a tree, by a circle of people standing in a yard.

"I read about the 'walking meditations' of the Tibetan Buddhists; I read of the Catholic faithful in the American Southwest spending Holy Week en route to Chimayo, the old mission in the New Mexico highlands. Chatwin tells us that among the Sufi siyahat or 'errance' — the action or rhythm of walking — is used as a technique for dissolving the attachments of the world and allowing men to lose themselves in God. A Sufi manual cited by Chatwin, the Kash-al Mahjab, says that the Sufi dervish aims to become a 'dead man walking': one whose body stays alive on earth yet whose soul is already in heaven. Toward the end of his journey the dervish becomes one with the Way — becomes, that is, part of the landscape over which he or she is passing. . . .

"I read about the Eastern Orthodox pilgrim who walked thousands and thousands of miles across old Russia chanting to himself the Jesus Prayer: 'Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me.' He chanted to still his mind, to silence his self; he aimed to internalize the prayer, to make it resonate with his heartbeat so that in every breath he would sense the presence of Jesus. Measuring his mercies into his stride, into his breath, into his pulse, he aimed to free himself from awareness of the self and its limited concerns and desires."