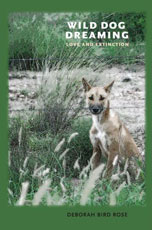

Deborah Bird Rose is Professor in the Centre for Research on Social Inclusion at Macquarie University, Sydney. In many parts of Australia, wild dogs, known as dingoes, are being shot and poisoned to such an extent that they are facing extinction. For aboriginals, dingoes are kin. Australian actor and philosopher David Gulpilil explains: "We are brothers and sisters of the world. Doesn't matter if you're bird, snake, fish, kangaroo: One Red Blood." This spiritual perception of the interspecies connection has been replaced by a dualism which justifies the creation of a great divide between people and wild animals. Australians who buy into this philosophy were happy to see dingo-proof fences erected to protect sheep and cattle from these "pests." According to James Woodford, who has traveled the fence, it "is an ecological Berlin Wall comparable to the Great Wall of China."

According to Rose, the human beings who revel in killing dingoes are the real predators:

"The war against dingoes takes us into the shadow of death, where extinction is a near possibility. Dingo deaths are one ripple in the larger pattern of destruction that calls us to ask: Is eco-reconciliation nothing more than a wild and crazy dream? Is it necessary that all animals become either pets or enemies? Is there no room for the companionability of others who share with us the glories of life without being beholden to us in any particular way?"

The time has come for us to leave behind dualism and embrace cross-species connections, expanding the circle of our family and friends to every kind of creature that walks the face of the earth. Or as the philosopher Erazim Kohak tells us in this cogent book:

"Perhaps the most basic ecological experience is that of an audacious generosity, of daring to love all the suffering, perishing creation."