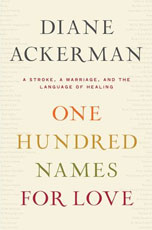

Diane Ackerman, bestselling author of A Natural History of Love and other books, married Paul West, a professor at Penn State who was 18 years older than she was. They both loved language and writing. One could say it was a true marriage of the minds as they did puzzles and dreamed up crazy and adorable pet names for each other (the title's meaning). In addition, Paul wrote her love notes for decades. Ackerman relished his talent for phrasemaking whereas she more often used imagery to define her experiences. She describes their household as being "saturated in wordplay."

When West suffered a stroke after kidney surgery at the age of 74, his brain was badly damaged. Doctors diagnosed him as having severe global aphasia — a near total loss of language and memory — and were not sure of his chances for recovery. Ackerman is stunned by the fragile and vulnerable condition of her husband but dedicates herself to being the best ally and caregiver that she can be in this crisis situation. "He'd joined the ranks of over 1 million Americans living with aphasia — a void of language, a frustrating perpetual tip-of-the-tongue memory loss, a mute torturer of words, a jumbler of lives."

Suddenly Paul has nothing to say except "mem," which serves as his greeting, his expression of anger or frustration, and his curse. Ackerman has no access to his thoughts or feelings and feels shut out and alone. Speech therapy begins and she finds after a while that it is not working all that well. Knowing a bit about the brain's complex workings and especially the nature of her husband's consciousness, she designs a language therapy program suitable to his character and needs.

One Hundred Names for Love is a brilliantly written and deeply touching account of the five-year ordeal Ackerman and her husband endure together. By the end of the book, he is able to write again, work on a book review and, for the first time since his stroke, make puns. Ackerman shares some notes for other caregivers for aphasics and recommends appreciation and humor, constraint-induced therapy, ignoring timetables, encouraging creativity, exercising the brain, and living more in the present.