We have become dull, numb, mushy, and untethered — and those are the first four chapter titles of this new book about how we’ve lost our connection to the physical world. This began not just in recent decades with the digital and virtual revolutions, but much earlier when mind was celebrated as lasting, versus the material, which was seen to be fleeting.

These problematic origins go back to Plato, according to author Sushma Subramanian. Plato defined the most important sense, vision, “as a way of experiencing the world that operates at a physical remove, [and] allows for cool reason.” Touch, for Plato, “is immediate and visceral … concerned with gut-level needs,” so he ranked it the least important.

Subramanian then weaves these ideas through the centuries. For example, in the early modern period, she explains: “The eye had long been associated with the intellect, so it became a dominant sense as the literacy rate rose at the dawn of the Enlightenment. Seeing overshadowed doing as the way people proclaimed their expertise. They no longer had to spend years apprenticing under the supervision of an expert, carefully training the intuition of their bodies. Instead, they read and took tests and received diplomas from prestigious houses of learning.”

The author is a researcher and a professor of journalism in the United States. She came to North America from India, where much of her family still resides. Often, she incorporates examples of her experiences and family in India to counter western norms of behavior regarding use of the senses.

“Touch is crucial to our capacity for basic movement, but that’s probably not what most of us think about when we imagine what it’s like to lose the sense of touch. What’s more likely to come to my mind is what it would be like to have none of the more delightful sensations of our lives — the caress of a loved one, the feeling of crawling into clean sheets, smooth sand under our feet, and the rumbling of a bike on a gravelly road. It’s those tickles and nudges from the universe that make us feel alive.”

Throw in how we’ve all come to live primarily on screens over the last quarter century, and what was a cultural assumption has become a way of living fait accompli, an assumed reality, whether or not it makes us healthy or happy.

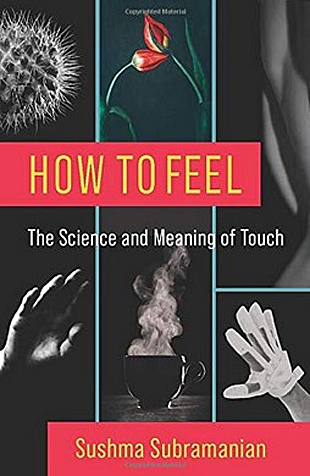

Subramanian wants to plant firmly in us the need for touch — of our world and each other. How to Feel is her title because she argues that unless we learn how to touch — maybe for the first time — we won’t really know how we feel. She makes a convincing case.