“dying is fine)but Death

?o

Baby

iwouldn’t like

Death if Death

were good…”

— e. e. cummings

“Holy mother forking shirtballs!” The four seasons (2016 – 2020) of the weekly series The Good Place have finished their run on NBC-TV and have moved on to DVD/Blu-Ray discs and streaming services like the NBC app, Netflix, and Hulu. Viewers can now binge the entire series or take a more leisurely approach to the 53 half-hour episodes. The scripts, directing, and acting are thoroughly engaging, with a philosophical understory unprecedented in the history of TV sitcoms. As a professor of philosophy, I was totally taken with the series and was not surprised to find that many of my colleagues were too. What follows are my reflections on The Good Place, the questions it raises and the teachings it explores. (If you are really averse to plot spoilers, you may want to return here after you have gotten into the series.)

Key questions arise during The Good Place’s four scintillatingly complex comedic seasons. What is the difference between the Good Place, the Bad Place, or the Medium Place, for that matter? More fundamentally, what gives meaning to the lives we live? And can philosophy provide the answers?

Todd May of Clemson University and Pam Hieronymi of UCLA were the philosophical consultants to the series’ creator Mike Shur. Both appear in character in the final episode, where May quotes himself: “Mortality offers meaning to the events of our lives, and morality helps us navigate that meaning.” Like e.e. cummings, May is an “immortality curmudgeon.” It is only because we die that we can create meaning for our lives. Is this what The Good Place suggests?

When Eleanor Shellstrop (Kristen Bell) dies, she is welcomed to the Good Place by Michael (Ted Danson), who introduces her to an idiosyncratic, colorful neighborhood he designed, where she is assigned to spend eternity. But a mistake has been made: Eleanor is greedy and self-centered and realizes she doesn’t deserve to be there. Soon three other mistakes are admitted. Chidi Anagonye (William Jackson Harper) is a diffident moral philosopher from Senegal, unable to act decisively. Tahani al-Jamil (Jameela Jamil) is a wealthy Indian socialite driven to philanthropy out of sibling rivalry. Then there is Jason Mendoza (Manny Jacinto), who is misidentified as a silent Buddhist hermit, when he is actually a thoroughly undereducated Jacksonville DJ dancer, drug dealer, and zany lowlife. Michael slyly pairs Eleanor with Chidi and Tahani with Jason as soulmates. Let the series and the fun begin.

Michael, the architect of this Good Place, is actually a demon in human form. He has paired the four together to antagonize each other eternally, as part of a demonstration project for the Bad Place: the goal is to let the humans torture each other. All the other characters populating Michael’s fake Good Place are demons too, taking on new roles after previously torturing human beings themselves. Michael requires the use of an Alexa-like omniscient being in human form named Janet (D’Arcy Cardin) who has the entire history of the universe in her memory and can also instantly provide whatever the four subjects of this diabolical experiment ask for. Janet is not a demon, but an angelic creation, stolen from the genuine Good Place to lend verisimilitude. Michael’s experiment in mutual psychological torture is answerable only to his boss, the archdemon Shawn (Marc Evan Jackson) who far prefers physical torture, snatching all the humans he can, like C. S. Lewis’ Screwtape.

The plot of The Good Place was adapted from French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit, performed in Paris in 1944 with permission from the Nazi occupation. There three moral/social failures, even in the eyes of Nazis, find themselves confined to being with each other forever and conclude: “Hell is — other people.” In Shur’s world Sartre’s premises get challenged. And the indecisive philosopher Chidi, along with the good Janet, become vehicles for moral edification. But Eleanor remains the hero of the tale.

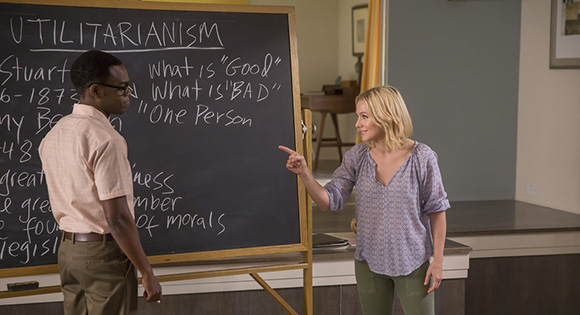

To protect her presumed identity and deserve her presence in the apparent Good Place, Eleanor decides to study philosophy with Chidi who gladly teaches her and eventually Tahani and Jason as well, along with a reformed Michael. Chidi expounds upon a full range of moral approaches displayed over the episodes: virtue ethics from Aristotle, deontology from Kant, consequentialism, utilitarianism, particularism, existentialism, nihilism, and several other "isms." Contemporary philosopher T. M. Scanlon’s contractualism has a privileged role to play. But which approach is the one to choose? How is one to act accordingly?

These different moral theories find their way onto Chidi’s whiteboard, where observant philosophers like myself are thrilled to see our colleagues listed along with the likes of Aristotle, Locke, Kant, Kierkegaard, in the same way physics fans of Big Bang Theory enjoyed seeing familiar or even jokey physics equations on that show's whiteboard. Over the course of four seasons of The Good Place, classical moral dilemmas long discussed by philosophers worm their way into the plots, such as “The Trolley Problem” in Chapter 19 (S 2, ep. 5).

Throughout the seasons, the four humans continue to bond together, instead of falling apart, whatever the provocations. They come to know each other’s moral limitations and yet help each other improve. At the end of the first season, Eleanor realizes they are in the Bad Place, psychologically torturing each other.

The plot accelerates as Michael erases their postmortem memories, reboots the cyborg Janet, and starts the experiment over and over again, hundreds of times. But in every iteration, Chidi eventually teaches moral philosophy to all of them. Eleanor and Chidi keep falling in love, just as Tahani is attracted to Jason as her polar opposite, though Jason, the very least of them, and angelic Janet marry their souls together. Michael eventually goes over to the Good side and stays there, like a Satan who returned to Heaven.

There are of course plots and subplots, varieties on the theme, leading to more memory cleansing and cyborg rebooting. The show is a metaphysical soap opera! A morally indifferent Judge shows up to adjudicate disputes between the Bad Place, the Good Place, and the four humans, with a desire on her part simply to eradicate humanity and give up the business entirely. Nonetheless, various experiments are tried. The Judge sends the humans back to Earth just before they died to see whether things would turn out differently. But the good Michael and Janet keep surreptitiously intervening with little gifts of grace to keep the four together, while Eleanor becomes a moral force of goodness on her own, until Shawn shows up, their cover blown.

It turns out the accounting department that counts up the credits and the debits of moral desert has so rigorous and rigid a scoring system that it proves impossible for mere mortals ever to qualify quantitatively for the Good Place, since no human being is perfect. Especially problematic are the unanticipated consequences of our most well-intended actions, even such as eating a tomato. The details of these episodes are entertaining and enlightening.

In the end the four humans arrive at the truly Good Place, with Eleanor and Chidi together forever, and Jason deeply in love with Janet, so often rebooted that she is more human than angelic. Tahani reconciles with her family and pursues a goal-oriented existence eternally. A philosophically and emotionally happy ending? Not quite.

T. M. Scanlon’s book What We Owe Each Other provides Michael Shur with the architecture undergirding the entire series. Derived from bits of Aristotle, Kant, Rawls, and others, Scanlon’s contractualism argues that the core of morality lies in a kind of social contract derived from respecting others’ moral points of view, with the task of finding “terms of justification that others could not reasonably reject.” Contrary to Sartre, morality is other people and that requires a reasoned consensus regarding what we owe each other.

After having lived several millennia in the truly Good Place, Eleanor finally finishes reading Scanlon and throws the book down in exasperation, reading aloud Scanlon’s last line from his tedious tome: “But we are not in a position to say, once and for all, what these terms should be. Working out the terms of moral justification is an unending task.” Not even an eternity will yield decisive moral clarity!

Were Chidi’s philosophy lectures and Scanlon’s text the key to enlightenment? Or was philosophy only a means for provoking something else entirely, something spiritual in character: learning to love one another selflessly? Over the course of their long journey to the really Good Place each of the characters makes sacrifices for the others, again and again: Tahani, Jason, and especially Chidi and Eleanor, even formerly demonic Michael and angelic Janet. When they sacrifice their self-interests this way, they don’t act by drawing out reflectively well-reasoned philosophical conclusions. They act from another motivation entirely.

What is going on here? It turns out that the Good Place, when you finally get there, is listless and boring, same old same old, millennium after millennium. It is hardly the place for perpetually singing God’s praises, especially because there is no God in the Good Place whatsoever. There is merely the work of a Good Place Administration, much like the bureaucracy of the Bad Place or the Accounting Department. This may prove perfectly satisfying to 21st century secularists who readily acknowledge evil, even devils, but never God or the Ground of Being. The moral task of choosing who gets admitted into the Good Place keeps getting increasingly complicated, given the unforeseen consequences of our actions. It is all too easy to condemn sinners or find fault with saints, but now humans at least have a better chance to pass their admission tests, since they can take them over and over again.

Happiness and contentment dull though overuse. The genuine Good Place neighborhood doesn’t seem to differ much from the false Good Place that Michael had designed. Human appetites remain the same. The philosophy classes in the Good Place continue, but there is no enlightenment at the end of the course, because there is no end to the course. There are only unending philosophical puzzles about the human condition and the choices we present one another under various circumstances (the fodder for philosophy departments everywhere). Philosophy was never the heart of the story after all. It was a device for discovering the possibility of selflessness in the course of human actions. Selfless love transcends everything that went before, from philosophical reflections to self-interested actions.

Unlike Sartre’s No Exit, Michael and Janet bypass celestial ennui and improve the Good Place by providing a way out, not a way to begin again as the four humans had done nearly a thousand times in their troubled journey there. The final exit offers nonexistence, where one vanishes into the cosmos upon exiting the Good Place.

This could have seemed to be a sort of Stoic suicide, where ineradicable moral suffering requires walking out of life, as Epictetus was fond of arguing that the door was always open. But unlike Stoic suicide when one returns one’s borrowed soul back to God, there is no governing God and there is no suffering in the Good Place.

The way out might have seemed to be an Epicurean recognition of our purely material existence. We are, after all, simply composed of atoms in motion in the void until the day our atoms disperse and we vanish out of sight. But the Epicurean dissolution into godless chaos is not a spiritually worthy exit either, worthy of walking away from a community of friends.

In the final episode, our four friends do take leave of one other. (The actors cried when they read through the final script.) Jason the comic existentialist is the first to exit the Good Place, fulfilled by a Madden NFL video game he finally mastered for his beloved Jacksonville Jaguars. Yet his parting from Janet is such sweet sorrow. Angelic Janet consoles Jason: the past and future blend into the present, which is where she abides. Jason will always remain with her, after he has vanished.

The denouement of the four seasons comes as Chidi gently tells his beloved Eleanor he is going to take the final exit too and vanish, after countless years of being blissfully together. Chidi turns to a classical Buddhist koan to explain, rather than a passage from Scanlon or May: “Picture a wave in the ocean … And then it crashes on the shore and it’s gone. But the water is still there. The wave was just a different way for the water to be, for a little while.”

The good Eleanor soon will follow Chidi, once her remaining moral tasks are done, and we watch her existence evanesce into a spark of grace. The formerly demonic Michael is given the gift of human life, after the fashion of the angel in Wim Wenders’ 1987 film Wings of Desire, so he can marvel at the trivia of human existence and try to earn his own way to the Good Place as another flawed human. But Tahani stays, taking on a perfect philanthropy by designing suitably familiar Good Place neighborhoods for other humans who pass their tests; hers is an eternal act of selflessness.

“Your time in the universe will end. It will be peaceful and your journey will be over.” This Buddhist solution to the problem of human existence offers a final twist beyond the script: there never was a need for a Good Place or a Bad Place, a place to go after we die, at all. There is only our present life. If we live it mindfully in the company of others and as selflessly as Eleanor learns to do, then our lives can become a spark to nudge those who come after us to follow this same course, riding waves of their own.

GOING DEEPER

Questions for Reflection:

- What do you imagine the Good Place might be like and how long would you want to be there?

- Does knowing that we are mortal encourage us to be moral?

- What does a life worth living look like?

- Is there a presence of God’s grace within our lives to nudge us to be good? When have you experienced it?

Recommended Reading:

- Todd May. Death. New York: Routledge, 2009John Martin Fischer. Death, Immortality, and Meaning in Life. New York: Oxford UP, 2019.

- Thich Nhat Hanh. Finding Our True Home: Living in the Pure Land Here and Now. Berkeley: Parallax Press, 2003.

- T. M. Scanlon. What We Owe Each Other. Cambridge: the Belknap Press of Harvard U.P., 1998.

David Glidden is professor emeritus of classics and philosophy at the University of California, Riverside. He is interested in the history of philosophy (especially Greco-Roman philosophers) and the spiritual life of philosophy as a practiced way of life.